Abstract

Background: Treatment with tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitors offers promising new opportunities to improve the health-related QOL of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in Denmark. As of September 2003, two such compounds — infliximab and etanercept — were registered for use by patients with RA. These drugs have shown the ability to reduce disease activity and to slow down or halt the development of new joint damage in otherwise treatment-resistant patients with RA. The acquisition cost of the drugs is high, with 1 year of treatment costing €9000–12 000 per patient.

Objective: The aim of this study was to assess the potential impact on the Danish healthcare budget of prescribing infliximab or etanercept to patients with RA.

Method: Two treatment implementation scenarios were investigated. In the progressive scenario, all patients newly diagnosed with RA were offered TNFα inhibitors as the drug of first choice. In the modest scenario, only patients with insufficient disease suppression by conventional therapy with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) were offered TNFα inhibitor therapy. The budget impact analysis, which was part of a Danish health technology assessment of TNFα inhibitors, focused on the number of patients offered treatment during a 5-year period and resource use related to drug and staff costs. Simple sensitivity analyses assessed the consequences of changing the drug dosage, the number of patients offered treatment and the rate of treatment cessation.

Results: The results suggested that both implementation strategies would impose additional costs per year on the Danish healthcare service, in the range of €67–188 million for the progressive scenario and €17–49 million for the modest scenario (price level August 2002). These costs represent between half and up to five times the amount currently used on treating patients with RA.

Conclusion: This analysis suggests that the introduction of TNFα inhibitors into the treatment regimen of patients with RA could pose a considerable financial burden on the Danish healthcare system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitors represent promising new treatment opportunities for patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (RA).[1] Before the introduction of TNFα inhibitors, patients insufficiently controlled with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) were usually also those most severely affected by the disease. Treatment with additional high-dose corticosteroids was the only option for these patients, with the attendant high risk of long-term adverse effects. The introduction of TNFα inhibitors has dramatically improved the situation for many of these patients.

As of September 2003, two types of TNFα inhibitors (infliximab and etanercept) were registered for use by patients with RA.[2] Adalimumab has since been released on the market as have other new biological compounds (e.g. anakinra).[3–5] In randomised clinical trials,[6–9] both infliximab and etanercept have shown the ability to reduce disease activity and to slow down or halt the development of new joint damage — a result not previously shown for DMARDs unless disease remission was achieved. However, the optimal dose and treatment intervals, the long-term adverse effects and the indications for use in early RA have not been finally determined yet for TNFα inhibitors.[10,11]

High acquisition costs are associated with both compounds. A Dutch study has estimated the cost of 1 year’s treatment to be €9000–12 000 per patient.[12] Given such a high treatment cost, concerns have been expressed about the ability of health services to finance this new type of treatment.[2] Such an issue can be addressed through a budget impact analysis.

An increasing number of studies have assessed the cost effectiveness of TNFα inhibitors.[13–20] In two studies,[13,16] the cost of intervention in subgroups of patients with RA was related to disease-specific indicators of effects (American College of Rheumatology 20 and 70 response criteria). Because of the use of these disease-specific indicators, however, the studies can only be used to compare cost effectiveness in relation to substituting treatments for patients with RA and not to compare cost-effectiveness with other interventions or patient groups. The other studies[14,15,17–20] assessed the cost per QALY and found that the estimated cost per QALY varied within a wide range. The earlier studies showed a cost-effectiveness rate of €30 000 per gained QALY, while in the more recent analyses this rate has fallen to below €10 000 per QALY.[11,21] While all economic studies involved assessments of cost effectiveness, none explicitly assessed the likely impact on the health-service bud-get.

Budget impact analysis is complementary to health economic evaluation.[22] Although the two types of analysis may use similar data, their focus and emphasis are different. An economic evaluation would typically assess ‘value for money’, while a budget impact analysis would assess affordability and issues relating to financing the service. Economic evaluations are typically conducted with a long-term perspective, whereas a budget impact analysis would apply a narrower time perspective and focus primarily on the financial consequences for the healthcare service. Costs and effects falling outside the health authority (e.g. in the social sector or on patients) and consequences in terms of production loss are disregarded in budget impact analysis, as they are believed to be beyond the primary interest of healthcare decision makers.

In clinical guidelines issued by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence in Great Britain, simple calculations of the likely budget impact of using infliximab and etanercept suggested that the total budget impact in England and Wales would be £55–75 million per year (€80–110 million).[23] A study based on the Oslo Rheumatoid Arthritis Register estimated the annual cost for the whole population of Norway (4 million people) to be approximately €14 million.[24] Both cost calculations were based on an average annual cost of treatment multiplied by the number of patients being offered treatment. Different implementation or treatment strategies were not considered, nor was the fact that some patients cease treatment due to lack of effect or undesirable adverse effects. Furthermore, neither study assessed the budgetary consequences of the long-term nature of the treatment (treatment extends over several years) and the accumulation over time of patients being offered treatment.

The aim of this study was to assess the likely impact on the health service budget of two different implementation strategies for TNFα inhibitors in the treatment of RA. The focus of the analysis was the Danish healthcare service, which serves a population of 5.2 million people. The analysis was based on an assumption that treatment with TNFα inhibitors was centralised to five hospital departments, each providing highly specialised rheumatological services. In line with current recommendations, privately practising rheumatologists and hospital departments that provide district rheumatology services would not be allowed to initiate treatment with TNFα inhibitors.[23]

Three implementation scenarios were defined. The baseline scenario reflected practice before the introduction of TNFα inhibitors, i.e. patients with RA were not treated with TNFα inhibitors but with current conventional therapy (DMARDs). Two alternative scenarios were defined, each with a different strategy for the use of TNFα inhibitors: (i) a progressive scenario, in which TNFα inhibitors were offered to all patients with RA as the drug of first choice (i.e. both newly diagnosed patients and those who have failed to respond well to DMARDs); and (ii) a modest and more evidence-based scenario, in which treatment with TNFα inhibitors was offered only to patients with insufficient response to or serious adverse effects from DMARD treatment.

The budget impact analysis focused on the number of patients who would be offered treatment with TNFα inhibitors, the additional staff that would be required and the incremental costs compared with current conventional therapy, i.e. the baseline scenario of treatment in terms of drugs, consumables and human resources.

Method

General Principles

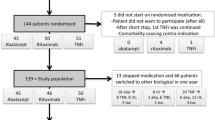

The analysis was based on explicit assumptions about the incidence and prevalence of Danish patients with RA who attended rheumatologists for treatment. Between 10% and 20% of patients treated by a rheumatologist were assumed to be eligible for treatment with TNFα inhibitors.[24] Based on these figures, and assumptions related to the different implementation strategies, the number of patients starting treatment with TNFα inhibitors over a 5-year period were calculated. The annual incremental treatment costs to the health services were modelled by taking into account patient characteristics (weight), drug type, dose and required personnel resources. A proportion of patients were expected to stop TNFα-inhibitor treatment because of lack of response, undesirable adverse effects or for other reasons. Based on these assumptions, the incremental cost of treatment and staff use in the two alternative scenarios were calculated at a national level. Different assumptions relating to the drug regimen and the number of patients offered treatment and ceasing treatment were tested in sensitivity analyses.

Baseline Population

The 2000 Danish national health survey asked respondents whether a medical doctor had diagnosed them as having RA. The results suggested that around 35 000 Danes had RA, corresponding to a prevalence of 0.8% among those aged 18 years and over. While this is a useful starting point, prevalence studies based on self-reported diagnosis are not the recommended source of information and a more appropriate method would be to determine the prevalence using specific population studies.[25] In other Nordic countries, the prevalence of RA appears to be between 0.35% and 0.51%.[26–28]

Based on unpublished observations of the annual number of patients with RA who had consultations with rheumatologists in one Danish county, an estimated annual total of 18 000 patients with RA were assumed to be under the care of Danish rheumatologists. This prevalence figure of 0.47% is similar to the prevalence found in other Nordic countries, but is lower than the reported 0.8% in the UK.[23] The incidence of RA in the adult Danish population was estimated to be 0.04%, based on the registrations of all newly diagnosed patients in a clinic for early arthritis in the same county. This rate corresponds to 1700 new cases a year and is similar to recent estimates of the number of patients who are potentially eligible for treatment with TNFα inhibitors.[24] For the purpose of simplification, the number of RA patients in rheumatological care was assumed to remain constant during the years considered (i.e. any demographic changes were disregarded).

Implementation Strategies

In the progressive implementation scenario, it was assumed that TNFα inhibitors would be the first treatment choice for all patients newly diagnosed with RA. This would represent an optimal pursuit for disease control, including minimisation of the risk of joint destruction. Among already-diagnosed patients, treatment would be offered only to those with an insufficient response to DMARDs, which was assumed to be 10–20% of the patients currently on DMARD treatment. In the calculation of costs over a 5-year period, 15% (the average of 10–20%) was chosen in order to simplify the calculations. Furthermore, in regard to when these patients would start treatment with TNFα inhibitors, a steady increase in the numbers was assumed. Due to lack of better data, it was postulated that one-half and one-quarter of the patients would begin treatment in years 1 and 2, respectively, while the remaining patients would start treatment in years 3–5. Over the 5-year period considered, all of the existing patients who failed to respond to traditional DMARD treatment would thus be offered treatment with TNFα inhibitors. In the subsequent years (year 6 and thereafter), only newly diagnosed patients would be offered treatment with TNFα inhibitors.

In the second strategy, the modest implementation scenario, treatment with TNFα inhibitors would not be offered as the drug of first choice to any patient. Instead, all patients (including those newly diagnosed) should have failed on DMARD therapy before being offered treatment with TNFα inhibitors. Because of earlier and more aggressive treatment with traditional DMARDs, it was assumed that only 10% of patients with newly diagnosed RA would not respond sufficiently to DMARD therapy and would thus need treatment with TNFα inhibitors. Half of these patients were assumed to begin treatment with TNFα inhibitors in the second year after diagnosis, a quarter of the patients would begin in the third year and the remaining quarter would begin in the fourth to fifth year. Among already diagnosed patients, the use of treatment with TNFα inhibitors was assumed to be identical to the progressive implementation scenario.

Cost of Treatment

Infliximab is infused intravenously under close clinical supervision, whereas patients on etanercept can inject themselves at home after a short instruction session. As the drug costs and methods of administration are different, the costs of the two regimens were analysed separately. For the sake of simplicity, both TNFα inhibitors were assumed to be given in combination with methotrexate, and patients who did not receive TNFα inhibitors were assumed to be treated with methotrexate. The incremental cost of medication was thus assumed to relate to treatment with TNFα inhibitors only. As the annual cost of treatment with methotrexate is low in comparison with the treatment cost of TNFα inhibitors, this simplification was expected to introduce minimal bias in the cost calculations.

Based on recommended dosages, infliximab treatment required nine infusions during the first year and six infusions in subsequent years. In the main analysis the dosage was assumed to be 3 mg/kg and the average patient was assumed to weigh 67kg. The average patient would thus receive 200mg infliximab per infusion. Infliximab would be provided in 100mg ampoules and the pharmacy cost (including the infusion kit) was assumed to be €583 per 100mg (based on local prices to hospital pharmacies, August 2002). Infusions were assumed to take place in a day hospital with groups of four patients being infused concomitantly to save personnel resources and drug wastage (infliximab is only provided in ampoules of 100mg). The infusion was assumed to be undertaken by a team consisting of a medical doctor (30 minutes/patient), a nurse (60 minutes/patient) and a secretary (40 minutes/patient) with total salary costs of €123 per patient per session (local estimate, August 2002). Consumables to infusion were costed at €2 per patient per session. As only marginal costs were considered, no contributions to the fixed cost (management, investment and maintenance of equipment and buildings) were included.

Etanercept is injected subcutaneously twice a week by the patients themselves. The recommended dose of 25mg twice weekly was used in the main analysis. The pharmacy price was assumed to be €158 per injection (price given by the Danish supplier, August 2002), which, together with the cost of patient instruction, amounted to an annual treatment cost of €16 559. An increase to thrice-weekly injections would increase the annual cost to €24 789.

In contrast to infliximab, which has only been proven useful in combination with methotrexate, etanercept can be used both alone and in combination with methotrexate. In the cost analysis, TNFα inhibitors were assumed to be used in combination with methotrexate. If TNFα inhibitors were used as monotherapy, an estimated saving of €100 per patient per year could be made (based on an expert assessment of the cost of administering methotrexate and the associated laboratory tests).

It was assumed in the analysis that the cost of DMARD treatment for newly diagnosed patients would be similar to that for existing RA patients.

Cessation of Treatment

A proportion of patients treated with TNFα inhibitors will cease treatment because of lack of drug efficacy, unacceptable adverse effects, death or other causes. There is as yet no reliable data on treatment cessation, but a published review of available articles and abstracts up to September 2002 produced the cessation rates for each drug alone (see table I).[29] Discontinuation of treatment was assumed to be evenly distributed throughout the year.

Proportion of RA patients who would begin tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitor treatment and then cease treatment during the first 5 years (cessation as % of patients who started treatment)[29]

It was further assumed that patients who ceased infliximab treatment would, on average, have received four infusions, while patients ceasing treatment with etanercept would, on average, have received 26 injections. The treatment costs for patients ceasing treatment during the first year were assumed to be €5190 for infliximab and €4214 for etanercept.

Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity of the numerical assumptions was assessed in univariate analysis by altering the data related to average dosages, patient flow patterns and cessation of treatment with TNFα inhibitors. The increased doses were assumed to be 5 mg/kg for infliximab and thrice-weekly injections for etanercept. Such variations in doses can be found in the dosages tested in clinical studies. The increased patient flow was 20% instead of 15% of already diagnosed patients who would be offered treatment with TNFα inhibitors. Both figures were based on clinical expert judgement. The cessation rates for both drugs were changed to zero, which represents the most optimistic assumption but is also relevant when assessing the cost of a treatment according to clinical recommendations.

Results

During the first year of the progressive implementation scenario, treatment would be offered to all newly diagnosed patients (1700 patients) and to 1223 of the already diagnosed RA patients (18 000 − 1700 = 16 300), as shown in table II. If infliximab was used as the TNFα inhibitor, 30% of the patients would stop treatment in the first year of treatment due to lack of effect, undesirable adverse effects or death (see table I). In this case, 510 and 367 patients in the newly diagnosed and already diagnosed groups, respectively, (877 patients in total) would stop the treatment during the first year, while the remaining patients (2046 in total) would continue beyond the first year. As the number of patients beginning treatment was assumed to be evenly distributed over the year, approximately 1023 full years of treatment (2046/2) would be required. The annual number of patients treated with TNFα inhibitors and the number of full-year treatments required are shown in table II for both types of TNFα inhibitors and the two implementation scenarios. The subsequent calculation of the resource use was based on these data.

The estimated resource use is shown in table III. The cost of medicine in the progressive implementation scenario using infliximab was estimated to be €16.5 million and staff costs were estimated to be €1.6 million, totalling €18.1 million for the first year. The annual costs increased during the subsequent years as accumulating numbers of patients were offered the treatment (both newly diagnosed patients and patients who had started treatment earlier and continued to be treated). The annual cost in the fifth year of implementation was estimated to be €67.3 million. If etanercept was used in the progressive scenario, the costs of the first year were estimated to be €22.6 million, rising to €125.6 million in the fifth year of implementation.

In the modest implementation scenario, the lower costs related primarily to fewer patients being offered treatment. In the first year, the total cost of infliximab and etanercept was estimated to be €7.6 and €9.5 million, respectively, and in the fifth year €16.9 and €32.0 million, respectively.

The cost differences between treatment with either infliximab or etanercept related mainly to differences in medication price, personnel use and the proportion of patients ceasing treatment. The results of the three simple sensitivity analyses are shown in table IV. An increased dosage of either medication would increase the unit costs per dose and would result in an increased annual cost of 47–53%. Different patterns of patient flows would result in an increased cost of 7–14% in the progressive implementation scenario and an increased cost of 33–37% in the modest implementation scenario. Assuming that all patients continued with the TNFα inhibitor treatment, annual costs would increase by 4–8% in the first year and 44–70% in the fifth year.

Discussion

This analysis illustrates that the introduction of TNFα inhibitors into the treatment of patients with RA poses a considerable financial burden on the healthcare system. The additional annual financial burden for the Danish healthcare service is estimated to be in the area of €67–188 million for a progressive implementation strategy and €17–49 million for a modest implementation strategy. It should be noted that the progressive implementation strategy is a theoretical scenario that can be interpreted as the upper limit for the cost. In practice, because of rationing, not all newly diagnosed patients would start treatment with TNFα inhibitors.

It has been estimated that the Danish healthcare sector annually spends at least €37 million (2000 prices) on the treatment of patients with RA.[29,30] The introduction of TNFα inhibitors according to the two specified strategies would thus require considerable additional resources corresponding to up to five times the amount that is currently used. Even with the modest implementation strategy, the additional costs would correspond to at least half the current spending on treatment for patients with RA less any savings resulting from reduced morbidity.

Except for the increased financial burden of the drug, the impact on the health system would not appear to be large. The extra staff requirement was estimated to be 1.5–5.9 full-time staff for the infliximab scenario and even less for the etanercept scenario. It should be no problem to absorb these additional staff into the five existing treatment centres.

As patients treated with TNFα inhibitors would require the same number of ambulatory consultations and laboratory tests as patients treated with traditional DMARDs, most of the extra costs relate to the additional drug purchase. The small additional staff cost relates mainly to the infusion of infliximab, where the infusion is monitored by a team in case of an acute allergic reaction. An infusion team is also assumed to be associated with reduced wastage of the drug. Other organisational forms could be envisaged and are likely to be associated with different costs.

Comparing these results with the Norwegian study (see introduction),[24] their first year cost appears to be broadly similar to that of the progressive scenario. However, as patients continue treatment for more than 1 year and because new patients begin treatment in subsequent years, the number of patients offered treatment will increase over time. Eventually, a steady-state situation will be reached where the number of new patients equals the number of patients ceasing treatment. This situation has not been modelled in the Norwegian study and may perhaps not be fully developed during the 5-year period modelled here. However, this analysis raises the important point that the first-year treatment cost is unlikely to equate to the costs in the following years, and the total budget impact will increase over time.

The source of financing may be an important issue to consider. In the Danish system, the cost of drugs administered at hospitals is financed by the hospitals, which are fully financed by taxation and not by user payment. At present, the TNFα inhibitors are solely administered by hospitals and are therefore funded only out of the hospital budget. However, it would seem reasonable that, in the long term, a self-administered medicine like etanercept would be available for patients in primary care. In this case, some of the drug expenses might be funded by the social security system, and a maximum user payment of €480 could be imposed according to current rules.

Savings that could arise from the use of TNFα inhibitors have not been taken into account in these calculations. If TNFα inhibitors can replace traditional DMARDs, a saving in the medicine budget might arise. The discontinuation of methotrexate would result in a saving of €100 per year per patient, which corresponds to a total saving of around €0.6 million, or a modest 3.5% of the additional cost. If treatment with TNFα inhibitors can substitute other, more expensive DMARDs, then these savings might be higher. However, most patients appear to benefit from a continuous DMARD treatment given concomitantly with TNFα inhibitors; concomitant treatment with immunosuppressive agents such as DMARDs probably also increases the efficacy of TNFα inhibitors.[3]

This analysis did not include other benefits resulting from the use of TNFα inhibitors, such as changes in resource consumption elsewhere in the healthcare service or in other sectors of the economy. A reduced need for joint replacements is likely to arise in the long term as a consequence of delayed or halted joint destruction. Such reductions in hospital costs are not included in this analysis as no reliable data could be found on the likely reduction in the rate of joint replacement for RA patients. However, in a Canadian modelling study, patients treated with infliximab and methotrexate were estimated to use €3600 less of other healthcare resources (excluding the cost of infliximab treatment) when compared with patients treated only with methotrexate (35% savings in direct treatment cost and 80% savings in indirect costs from loss of productivity).[31]

Unlike some of the earlier published budgetary analyses, the current study included the costs related to patients stopping treatment with TNFα inhibitors. Treatment discontinuation typically occurs due to either lack of drug efficacy or unacceptable adverse effects. Treatments that fail to provide acceptable effects may result in untimely treatment cessation. This would reduce both the total cost of the treatment and also reduce the achieved benefits. A drug regimen that results in a greater number of untimely treatment stops will thus appear to cost less, but the number of patients who benefit from the treatment will be lower and thus the overall cost effectiveness will be reduced. It has been assumed in this study that treatment discontinuation occurs after approximately 3 months. If treatment continues for longer than this, the costs will be higher than estimated here.

Adverse effects from TNFα inhibitors appear to be infrequent, but potentially life-threatening adverse effects such as anaphylactic shock can arise during infusion with infliximab, although until now no deaths have been reported.[32] With the current application of infliximab, where patients are observed during infusion, life-saving treatment can be given immediately when necessary, but having staff on stand-by for these situations increases the cost associated with the treatment. If it is found that TNFα inhibitors increase the risk of serious long-term complications (e.g. increased cancer risk), such additional costs should also be included.

The treatment regimen in the current analysis involves either infliximab or etanercept. Generally, however, patients who find treatment with DMARDs is unsuccessful, and who later discon-tinue treatment with a TNFα inhibitor due to adverse effects or inefficacy, are likely to be switched to another TNFα inhibitor or another biological agent. The two scenarios can then be perceived as the lower and upper ranges of the likely costs. In the event that no patients discontinue treatment with TNFα inhibitors, the costs would be comparable to those described in the sensitivity analysis with no cessation (see table IV). The annual cost would increase as more and more patients are treated with the expensive therapy. Under this assumption, only death or serious health deterioration would be reasons for treatment cessation. With the growing numbers of elderly people and perhaps the increasing prevalence of patients treated with TNFα inhibitors, the healthcare service would face a further financial challenge.

It is unlikely that the high additional costs of treatment with TNFα inhibitors could in the short-term be funded by simple reallocation within existing budgets for treatment of patients with RA. New resources would have to be found either by reallocation from other patient groups or from reallocation from other sectors of the economy. When discussing reallocation of resources, it is necessary to examine the relative value for money from treatment with TNFα inhibitors in comparison with other competing alternatives. In the modest implementation scenario, patients are offered TNFα inhibitors only when traditional DMARDs have failed. However, as TNFα inhibitors at present represent the only available treatment option for this group of patients, some decision-makers may be less likely to strive for value for money. The presence of a new and apparently effective treatment option would also naturally create demand from rheumatologists who would want to offer the treatment to their patients. Decision-makers responsible for health budgets need to take such pressures into consideration.

Several studies have assessed the value for money of TNFα inhibitors in the treatment of patients with RA. It is of some concern that these studies present such widely differing estimates of incremental cost per QALY, ranging from €3000 to €130 000. If the high cost per QALY figure is true, then treatment with TNFα inhibitors may be fairly cost ineffective in comparison with many other treatments. However, if the low cost per QALY figure is true, then treatment may well lie within the range that decision-makers are willing to pay for a QALY. It seems likely, however, that decisions of which treatment strategy to follow and to whom it should be offered will be taken on incomplete knowledge of cost effectiveness. These decisions, therefore, require careful consideration.

In accordance with recommendations,[22] this budget impact analysis has been restricted to a time period of 5 years. After 5 years, a steady-state situation may arise in the moderate implementation scenario but not in the progressive implementation strategy. Considering the general rapid development of new treatment options, however, changes in treatment indications could occur within 5 years that would alter the patient flow. If future clinical studies confirm the current expectations that early, aggressive treatment that includes TNFα inhibitors can dramatically change the prognosis of RA, and that there will be few serious long-term adverse effects, then the use of the drug might be less restricted. Future drug costs might change due to increased competition and economies of scale (where more patients are offered treatment). Whether such an effect might be offset by the availability of yet new products with even more promising effects remains to be seen.

Conclusion

This analysis has illustrated that the introduction of TNFα inhibitors into the treatment regimen of patients with RA could pose a considerable financial burden on the Danish healthcare system. The analysis highlights the financial challenges that will be posed on healthcare systems when these new treatment regimens are introduced. The analysis has suggested that the financial resources required might be considerably larger than the amount that the hospital care system already uses on this particular group of patients.

References

Lee DM, Weinblatt ME. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2001; 358 (9285): 903–11

Taylor PC. Antibody therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2003; 3 (3): 323–8

O’Dell JR. Therapeutic strategies for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2004; 350 (25): 2591–602

Messori A, Santarlasci B, Vaiani M. New drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2004; 351 (9): 937–8

Olsen NJ, Stein CM. New drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2004; 350 (21): 2167–79

Maim R, St Clair EW, Breedveld F, et al. Infliximab (chimeric anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody) versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving concomitant methotrexate: a randomised phase III trial. ATTRACT Study Group. Lancet 1999; 354 (9194): 1932–9

Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DM, St Clair EW, et al. Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: antitumor necrosis factor trial in rheumatoid arthritis with concomitant therapy study group. N Engl J Med 2000; 343 (22): 1594–602

Weinblatt ME, Kremer JM, Bankhurst AD, et al. A trial of etanercept, a recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor: Fe fusion protein, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate. N Engl J Med 1999; 340 (4): 253–9

Moreland LW, Schiff MIL Baumgartner SW, et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1999; 130 (6): 478–86

Clime G, Voules S, Watts R. Dose reduction of etanercept: can we treat more patients using a fixed budget? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003; 42 (4): 600–1

Kavanaugh A, Cohen S, Cush JJ. The evolving use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2004; 31 (10): 1881–4

Nuijten MJ, Engelfriet P, Duijn K, et al. A cost-cost study comparing etanercept with infliximab in rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacoeconomics 2001; 19 (10): 1051–64

Choi HK, Seeger JD, Kuntz KM. A cost-effectiveness analysis of treatment options for patients with methotrexate-resistant rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43 (10): 2316–27

Bansback N, Brennan A, Ghatnekar O. The cost effectiveness of adalimumab in the treatment of moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis patients in Sweden [published online 2004 Nov doi:lo116/ard/s004.027565]. Ann Rheum Dis 2004

Brennan A, Bansback N, Reynolds A, et al. Modelling the costeffectiveness of etanercept in adults with rheumatoid arthritis in the UK. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004; 43 (1): 62–72

Choi HK, Seeger JD, Kuntz KM. A cost effectiveness analysis of treatment options for methotrexate-naive rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2002; 29 (6): 1156–65

Jobanputra P, Barton P, Bryan S, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of new drug treatments for rheumatoid arthritis: etanercept and infliximab. Birmingham: University of Birmingham, National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2001

Wong JB, Singh G, Kavanaugh A. Estimating the cost-effectiveness of 54 weeks of infliximab for rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med 2002; 113 (5): 400–8

Kobelt G, Jonsson L, Young A, et al. The cost-effectiveness of infliximab (Remicade®) in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in Sweden and the United Kingdom based on the AT TRACT study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003; 42 (2): 326–35

Jobanputra P, Barton P, Bryan S, et al. The effectiveness of infliximab and etanercept for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technology Assessment 2002; 6 (21): 1–110

Lyseng-Williamson KA, Plosker GL. Etanercept: a pharmacoeconomic review of its use in rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacoeconomics 2004; 22 (16): 1071–95

Trueman P, Drummond M, Hutton J. Developing guidance for budget impact analysis. Pharmacoeconomics 2001; 19 (6): 609–21

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guidance on the use of etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: technology appraisal guidance. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002: 36

Kvien TK, Uhlig T, Kristiansen IS. Criteria for TNF-targeted therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: estimates of the number of patients potentially eligible. Drugs 2001; 61 (12): 1711–20

Kvien TK, Glennas A, Knudsrod OG, et al. The validity of selfreported diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis: results from a population survey followed by clinical examinations. J Rheumatol 1996; 23 (11): 1866–71

Riise T, Jacobsen BK, Gran IT. Incidence and prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the county of Troms, northern Norway. J Rheumatol 2000; 27 (6): 1386–9

Uhlig T, Kvien TK, Glennas A, et al. The incidence and severity of rheumatoid arthritis, results from a county register in Oslo, Norway. J Rheumatol 1998; 25 (6): 1078–84

Simonsson M, Bergman S, Jacobsson LT, et al. The prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in Sweden. Scand J Rheumatol 1999; 28 (6): 340–3

Sundhedsstyrelsen - Center for Evaluering og Teknolgivurdering. Leddegigt - Medicinsk teknologivurdering of diagnostik og behandling [in Danish with English summary and conclusion]. Medicinsk Teknologivurdering 2002; 4 (2): 1-200

Sorensen J. Health care costs attributable to the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumato J 2004; 33 (6): 399–404

Kavanaugh A, Heudebert G, Cush J, et al. Cost evaluation of novel therapeutics in rheumatoid arthritis (CENTRA): a decision analysis model. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1996; 25 (5): 297–307

Scheinfeld N. A comprehensive review and evaluation of the side effects of the tumor necrosis factor alpha blockers etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab. J Dermatol Treat 2004; 15 (5): 280–94

Acknowledgements

This study was undertaken as part of a national health technology assessment initiated by the Danish Centre for Evaluation and Health Technology Assessment (DACEHTA). Lis Smedegaard Andersen acted as clinical secretary for the panel undertaking the technology assessment, and Jan Sørensen was chairman of the health economic working group. Comments from members of the project group, the peer reviewers and the editor are gratefully acknowledged. Claire Gudex has contributed to the preparation of the paper for publication. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sørensen, J., Andersen, L.S. The case of tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitors in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacoeconomics 23, 289–298 (2005). https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200523030-00008

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200523030-00008