-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

A. J. K. Östör, C. A. Richards, A. T. Prevost, C. A. Speed, B. L. Hazleman, Diagnosis and relation to general health of shoulder disorders presenting to primary care, Rheumatology, Volume 44, Issue 6, June 2005, Pages 800–805, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keh598

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Objectives. To prospectively evaluate the incidence, spectrum of disease and relation to general health of shoulder disorders in primary care.

Methods. Patients presenting with shoulder pain to two large general practices in the Cambridge area over a 1-month period were invited to participate. After consulting their general practitioner, patients were administered a demographic information questionnaire, a shoulder pain and disability index (SPADI) and a short form 36 (SF-36) health survey. Subsequent review in a clinic held by a rheumatology registrar every 2 weeks was undertaken.

Results. The sex- and age-standardized incidence of shoulder pain was 9.5 per 1000 (95% confidence interval 7.9 to 11.2 per 1000). Rotator cuff tendinopathy was found in 85%, signs of impingement in 74%, acromioclavicular joint disease in 24%, adhesive capsulitis in 15% and referred pain in 7%. On the SPADI the mean disability subscale score was 45 (95% confidence interval 41 to 50) and the mean pain score was 58 (95% confidence interval 53 to 62) (range 0 to 100). Evaluation of general health status using the SF-36 showed the difference between population norms and those with shoulder pain was significant in six of the eight domains, being especially marked (greater than 20 point reduction) for emotional role, physical function and physical role.

Conclusion. Shoulder pain, most commonly due to rotator cuff tendinopathy, is associated with significantly reduced health when measured by both specific and generic means. Effort towards prevention and early intervention in these complaints is warranted.

Soft tissue disorders are common, disabling and a strain on health-care resources. Shoulder pain has been found to be the second most frequent acute musculoskeletal complaint presenting in general practice and the third most common site of musculoskeletal pain in the community [1]. In addition, neck/shoulder disorders are a frequent cause of work absenteeism accounting for around 18% of all claims for sickness benefits in Scandinavia [2].

There is increasing interest in defining the disability associated with shoulder disease and its resultant handicap due to a paucity of information regarding the impact of such disorders on general health status. This study was designed to estimate the incidence, spectrum of disease and relation to general health of shoulder complaints presenting to primary care where these disorders are most frequently encountered.

Full ethical approval was granted for this study by the Addenbrooke's Hospital Ethics Committee, Cambridge and informed patient consent was obtained from all participants.

Patients and methods

Over a 12-month period patients who presented to their primary care physician with an episode of shoulder pain were recruited to two general practices in the Cambridge area (17 000 patients with a mean adult age representative of a typical UK practice). These patients were then referred to a ‘rapid access’ rheumatology clinic held within the practices by a rheumatology registrar every 2 weeks. A single rheumatology registrar (AO) trained in shoulder examination undertook all the assessments and a diagnosis was made based on the clinical evaluation. The diagnostic categories employed were drawn from widely accepted clinical tests for specific shoulder lesions, including those recommended by Cyriax [3] and the Southampton examination schedule [4] (Table 1).

Tests for examination of the shoulder

| Test . | Description . |

|---|---|

| Empty can test (supraspinatus) | The shoulder is abducted to 90° then internally rotated and brought into 30° forward flexion by the examiner, with thumb pointing downwards. The patient abducts the arm against the examiner's resistance |

| Resisted external rotation (infraspinatus and teres minor) | External rotation resisted with the patient's arm at the side, externally rotated 20° and the elbow flexed to 90° |

| Lift off test (subscapularis) | The dorsal aspect of the hand is placed on the ipsilateral buttock and the hand is then lifted off the buttock by 1–2′′. The hand is then lifted further against the resistance applied by the examiner |

| Yergason's test (long head of biceps) | With the arm by the side and the forearm flexed to 90° the forearm is supinated against resistance |

| Speed's test (long head of biceps) | With the elbow fully extended and the arm in 30° of flexion further flexion is resisted by the examiner |

| Hawkins–Kennedy impingement test | With the patient standing the arm is abducted to 90° and forward flexed to 45°. The arm is then forcibly internally rotated |

| Acromioclavicular joint assessment | With patient seated the examiner passively adducts the arm at 90° abduction across the chest. Alternative test: with the patient standing the examiner passively adducts the extended arm in front of the body |

| Drop arm test (rotator cuff rupture) | The examiner passively abducts the arm to 90° with subsequent active adduction |

| Test . | Description . |

|---|---|

| Empty can test (supraspinatus) | The shoulder is abducted to 90° then internally rotated and brought into 30° forward flexion by the examiner, with thumb pointing downwards. The patient abducts the arm against the examiner's resistance |

| Resisted external rotation (infraspinatus and teres minor) | External rotation resisted with the patient's arm at the side, externally rotated 20° and the elbow flexed to 90° |

| Lift off test (subscapularis) | The dorsal aspect of the hand is placed on the ipsilateral buttock and the hand is then lifted off the buttock by 1–2′′. The hand is then lifted further against the resistance applied by the examiner |

| Yergason's test (long head of biceps) | With the arm by the side and the forearm flexed to 90° the forearm is supinated against resistance |

| Speed's test (long head of biceps) | With the elbow fully extended and the arm in 30° of flexion further flexion is resisted by the examiner |

| Hawkins–Kennedy impingement test | With the patient standing the arm is abducted to 90° and forward flexed to 45°. The arm is then forcibly internally rotated |

| Acromioclavicular joint assessment | With patient seated the examiner passively adducts the arm at 90° abduction across the chest. Alternative test: with the patient standing the examiner passively adducts the extended arm in front of the body |

| Drop arm test (rotator cuff rupture) | The examiner passively abducts the arm to 90° with subsequent active adduction |

Tests for examination of the shoulder

| Test . | Description . |

|---|---|

| Empty can test (supraspinatus) | The shoulder is abducted to 90° then internally rotated and brought into 30° forward flexion by the examiner, with thumb pointing downwards. The patient abducts the arm against the examiner's resistance |

| Resisted external rotation (infraspinatus and teres minor) | External rotation resisted with the patient's arm at the side, externally rotated 20° and the elbow flexed to 90° |

| Lift off test (subscapularis) | The dorsal aspect of the hand is placed on the ipsilateral buttock and the hand is then lifted off the buttock by 1–2′′. The hand is then lifted further against the resistance applied by the examiner |

| Yergason's test (long head of biceps) | With the arm by the side and the forearm flexed to 90° the forearm is supinated against resistance |

| Speed's test (long head of biceps) | With the elbow fully extended and the arm in 30° of flexion further flexion is resisted by the examiner |

| Hawkins–Kennedy impingement test | With the patient standing the arm is abducted to 90° and forward flexed to 45°. The arm is then forcibly internally rotated |

| Acromioclavicular joint assessment | With patient seated the examiner passively adducts the arm at 90° abduction across the chest. Alternative test: with the patient standing the examiner passively adducts the extended arm in front of the body |

| Drop arm test (rotator cuff rupture) | The examiner passively abducts the arm to 90° with subsequent active adduction |

| Test . | Description . |

|---|---|

| Empty can test (supraspinatus) | The shoulder is abducted to 90° then internally rotated and brought into 30° forward flexion by the examiner, with thumb pointing downwards. The patient abducts the arm against the examiner's resistance |

| Resisted external rotation (infraspinatus and teres minor) | External rotation resisted with the patient's arm at the side, externally rotated 20° and the elbow flexed to 90° |

| Lift off test (subscapularis) | The dorsal aspect of the hand is placed on the ipsilateral buttock and the hand is then lifted off the buttock by 1–2′′. The hand is then lifted further against the resistance applied by the examiner |

| Yergason's test (long head of biceps) | With the arm by the side and the forearm flexed to 90° the forearm is supinated against resistance |

| Speed's test (long head of biceps) | With the elbow fully extended and the arm in 30° of flexion further flexion is resisted by the examiner |

| Hawkins–Kennedy impingement test | With the patient standing the arm is abducted to 90° and forward flexed to 45°. The arm is then forcibly internally rotated |

| Acromioclavicular joint assessment | With patient seated the examiner passively adducts the arm at 90° abduction across the chest. Alternative test: with the patient standing the examiner passively adducts the extended arm in front of the body |

| Drop arm test (rotator cuff rupture) | The examiner passively abducts the arm to 90° with subsequent active adduction |

The assessment included a full history of shoulder pain, the completion of a demographic information questionnaire, a shoulder pain and disability index (SPADI) [5] and a short form-36 health survey (SF-36) [6] followed by a physical examination including special tests for shoulder disorders (Table 1). A diagnosis was recorded and treatment or further investigation as deemed appropriate by the investigator was undertaken. The history included questions regarding shoulder pain at night or whilst doing overhead activities, any associated pins and needles, neck pain, previous shoulder pain and whether there had been any previous treatment such as with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroid injections or physiotherapy. The examination included assessment for deformity, tenderness, painful arc and passive external rotation. In addition, an assessment was made of the integrity of the rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus and subscapularis) according to the criteria of Cyriax [3], and assessment of the long head of biceps. Furthermore, assessment was made for signs of impingement and acromioclavicular (AC) joint disorder.

A diagnosis of rotator cuff tendinosis was made if, on stressing the rotator cuff by applying a resistive force, the patient complained of pain in one or more portions of the rotator cuff. A diagnosis of rotator cuff tear was made if weakness elicited by applying a resistive force was found in one or more of the rotator cuff muscles [3]. A complete rupture was diagnosed if there was minimal active movement but intact passive movement. Bicipital tendonitis was diagnosed if there was a history of anterior shoulder pain with specific tenderness in the bicipital groove supported by specialized tests for this lesion (Speed's and Yergason's tests). Adhesive capsulitis was diagnosed if there was global restriction of all shoulder movement both passive and active with external rotation reduced by at least 50% compared with the normal side in the absence of bony restriction [7]. In patients with global restriction of shoulder movement plain X-ray was used to exclude degenerative disease. Impingement was diagnosed with a positive Hawkins–Kennedy test [8]. Fibromyalgia was diagnosed if the patient fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology criteria [9] and other soft tissue lesions were diagnosed in the presence of specific tender spots over the shoulder musculature (deltoid, axillary or periscapular) without fulfilling the criteria for fibromyalgia.

Pathology of the AC joint was diagnosed if there was local pain and tenderness in the region of the AC joint, a high arc of pain (development of pain upon abducting the arm >120°) was present or if any of the tests for AC joint disease were positive (Table 1). Primary osteoarthritis of the glenohumoral joint was confirmed radiologically. Referred pain from the neck was diagnosed if there was a history of pain radiating from the cervical spine into the appropriate dermatome (C5/6) with or without restricted cervical spine movement.

The SPADI, a validated measure [10], was utilized to assess shoulder-specific disability alongside the SF-36 questionnaire which has been utilized to measure general health in a variety of medical conditions. The SPADI questionnaire consists of five pain and eight disability items each measured on a visual analogue scale (range 0 to 100), where 0 represents no pain or disability and 100 represents maximal pain or disability. Pain and disability subscales are calculated as the mean of the corresponding items. The SPADI total scale is calculated as the simple average of the pain and disability subscales.

The results obtained from the SF-36 were compared with those obtained from the Health Survey for England (HSE) 1996 [11]. This survey was carried out nationally on a population of over 16 000 people aged over 16 yr. The sample was drawn randomly using postcodes and the participants completed the SF-36 as a self-completion questionnaire. Other population studies have been carried out in England using SF-36 to produce population norms, including the British Omnibus Survey 1992 [12] and The Oxford (Central England) Healthy Life Survey 1991–1992 [13], but the HSE study matched our sample most closely in terms of age distribution. The examination was carried out blind to the results of the SPADI and SF-36.

Statistical analysis

The annual incidence of shoulder complaints was defined as the number of cases presenting for review by the registrar in the 12 months of the study divided by the number of adults recorded on the list of the practices. The method of direct standardization was used to standardize the incidence of shoulder complaints to the sex and age distribution of England and Wales in 2002 [14] using age groups 18–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74 and 75 and over. A 95% confidence interval for standardized incidence was calculated using the method of weighted sums of Poisson parameters in combination with the χ2 method [15]. The same methods were used for the incidence of diagnoses. Internal consistency of the SPADI subscales was assessed using Cronbach's alpha coefficient and interpreted as ‘very good’ for coefficients in the range 0.80 to 0.90 [16].

Age-specific normative mean scores with standard errors for each SF-36 domain were obtained from the Health Survey for England [11]. These were applied to the age distribution of the study sample to obtain an overall normative mean score with its standard error for each domain. The observed and normative mean scores were compared using an unpaired two-sample t-test stratified by age group, using the age-specific means and standard errors in the two studies. Partial correlation adjusting for age was used to assess the strength of association between the specific SPADI measure and the general SF-36 pain domains. Confidence intervals for correlation coefficients were obtained using the Fisher transformation method [17].

Results

Over a 12-month period 131 patients were reviewed comprising 69 men (53%) and 62 women (47%) resulting in a sex- and age-standardized incidence of 9.5 per 1000 (95% confidence interval 7.9–11.2 per 1000). It was estimated that the proportion of eligible patients not referred to the rapid access clinic was less than 10% of the total number. The precise number of ‘missed’ cases was undetermined, however, due to difficulty in establishing true numbers retrospectively from medical record diagnoses.

The mean age of the patients was 57 yr (range 18–87 yr) with a median duration of symptoms at review of 10 weeks (range 1–208 weeks). The right shoulder was affected solely in 72 (55%) patients, the left solely in 50 (38%) and both in 9 (7%). A precipitating incident was reported by 41 (34%) patients, no relation to trauma was reported by 47 (38%) patients and 35 (29%) didn't know. Rotator cuff tendinopathy was found in 112 (85%) patients, impingement in 97 (74%), acromioclavicular joint disease in 31 (24%) patients, adhesive capsulitis in 20 (15%) patients and referred pain in 9 (7%) (Table 2). In 77% of patients more than one diagnosis was made (Table 3).

Diagnoses made by researcher: composition and incidence

| Diagnosis . | Total numbera (percentage) of subjects . | Standardized incidenceb per thousand (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|

| Any shoulder complaint | 131 (100%) | 9.5 (7.9–11.2) |

| Rotator cuff tendinopathy | 112 (86%) | 8.1 (6.7–9.8) |

| Impingement | 97 (74%) | 6.7 (5.4–8.2) |

| Acromioclavicular disease | 40 (31%) | 2.9 (2.1–3.9) |

| Adhesive capsulitis | 20 (16%) | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) |

| Referred pain | 8 (6%) | 0.6 (0.2–1.1) |

| Diagnosis . | Total numbera (percentage) of subjects . | Standardized incidenceb per thousand (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|

| Any shoulder complaint | 131 (100%) | 9.5 (7.9–11.2) |

| Rotator cuff tendinopathy | 112 (86%) | 8.1 (6.7–9.8) |

| Impingement | 97 (74%) | 6.7 (5.4–8.2) |

| Acromioclavicular disease | 40 (31%) | 2.9 (2.1–3.9) |

| Adhesive capsulitis | 20 (16%) | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) |

| Referred pain | 8 (6%) | 0.6 (0.2–1.1) |

aSome subjects were given more than one diagnosis.

bDirectly standardized incidence is obtained by applying the sex- and age-specific incidence rates from the study to census population data (see Patients and methods). Study numerators for any shoulder complaint by age group in males (m) and females (f): 18–44 (m = 20, f = 9), 45–54 (m = 12, f = 12), 55–64 (m = 18, f = 22), 65–74 (m = 13, f = 12), 75+ (m = 6, f = 7) with corresponding study denominators 3306, 3087, 1180, 1199, 1040, 1029, 689, 708, 542, 815 and census denominators (thousands) 9900, 9922, 3350, 3406, 2863, 2945, 2066, 2325, 1486, 2513.

Diagnoses made by researcher: composition and incidence

| Diagnosis . | Total numbera (percentage) of subjects . | Standardized incidenceb per thousand (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|

| Any shoulder complaint | 131 (100%) | 9.5 (7.9–11.2) |

| Rotator cuff tendinopathy | 112 (86%) | 8.1 (6.7–9.8) |

| Impingement | 97 (74%) | 6.7 (5.4–8.2) |

| Acromioclavicular disease | 40 (31%) | 2.9 (2.1–3.9) |

| Adhesive capsulitis | 20 (16%) | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) |

| Referred pain | 8 (6%) | 0.6 (0.2–1.1) |

| Diagnosis . | Total numbera (percentage) of subjects . | Standardized incidenceb per thousand (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|

| Any shoulder complaint | 131 (100%) | 9.5 (7.9–11.2) |

| Rotator cuff tendinopathy | 112 (86%) | 8.1 (6.7–9.8) |

| Impingement | 97 (74%) | 6.7 (5.4–8.2) |

| Acromioclavicular disease | 40 (31%) | 2.9 (2.1–3.9) |

| Adhesive capsulitis | 20 (16%) | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) |

| Referred pain | 8 (6%) | 0.6 (0.2–1.1) |

aSome subjects were given more than one diagnosis.

bDirectly standardized incidence is obtained by applying the sex- and age-specific incidence rates from the study to census population data (see Patients and methods). Study numerators for any shoulder complaint by age group in males (m) and females (f): 18–44 (m = 20, f = 9), 45–54 (m = 12, f = 12), 55–64 (m = 18, f = 22), 65–74 (m = 13, f = 12), 75+ (m = 6, f = 7) with corresponding study denominators 3306, 3087, 1180, 1199, 1040, 1029, 689, 708, 542, 815 and census denominators (thousands) 9900, 9922, 3350, 3406, 2863, 2945, 2066, 2325, 1486, 2513.

Number of diagnoses

| Diagnosis . | Number . |

|---|---|

| Tendinosis + impingement | 75 (57%) |

| Tendinosis only | 21 (16%) |

| Tendinosis + impingement + acromioclavicular disease + adhesive capsulitis | 8 (6%) |

| Tendinosis + impingement + adhesive capsulitis | 2 (2%) |

| Tendinosis + impingement + referred pain | 6 (5%) |

| Acromioclavicular disease + adhesive capsulitis | 4 (3%) |

| Impingement only | 1 (1%) |

| Impingement + acromioclavicular disease + adhesive capsulitis | 4 (3%) |

| Impingement + acromioclavicular disease | 1 (1%) |

| Referred pain only | 2 (2%) |

| No diagnosis | 6 (5%) |

| Total | 131 (100%) |

| Diagnosis . | Number . |

|---|---|

| Tendinosis + impingement | 75 (57%) |

| Tendinosis only | 21 (16%) |

| Tendinosis + impingement + acromioclavicular disease + adhesive capsulitis | 8 (6%) |

| Tendinosis + impingement + adhesive capsulitis | 2 (2%) |

| Tendinosis + impingement + referred pain | 6 (5%) |

| Acromioclavicular disease + adhesive capsulitis | 4 (3%) |

| Impingement only | 1 (1%) |

| Impingement + acromioclavicular disease + adhesive capsulitis | 4 (3%) |

| Impingement + acromioclavicular disease | 1 (1%) |

| Referred pain only | 2 (2%) |

| No diagnosis | 6 (5%) |

| Total | 131 (100%) |

Number of diagnoses

| Diagnosis . | Number . |

|---|---|

| Tendinosis + impingement | 75 (57%) |

| Tendinosis only | 21 (16%) |

| Tendinosis + impingement + acromioclavicular disease + adhesive capsulitis | 8 (6%) |

| Tendinosis + impingement + adhesive capsulitis | 2 (2%) |

| Tendinosis + impingement + referred pain | 6 (5%) |

| Acromioclavicular disease + adhesive capsulitis | 4 (3%) |

| Impingement only | 1 (1%) |

| Impingement + acromioclavicular disease + adhesive capsulitis | 4 (3%) |

| Impingement + acromioclavicular disease | 1 (1%) |

| Referred pain only | 2 (2%) |

| No diagnosis | 6 (5%) |

| Total | 131 (100%) |

| Diagnosis . | Number . |

|---|---|

| Tendinosis + impingement | 75 (57%) |

| Tendinosis only | 21 (16%) |

| Tendinosis + impingement + acromioclavicular disease + adhesive capsulitis | 8 (6%) |

| Tendinosis + impingement + adhesive capsulitis | 2 (2%) |

| Tendinosis + impingement + referred pain | 6 (5%) |

| Acromioclavicular disease + adhesive capsulitis | 4 (3%) |

| Impingement only | 1 (1%) |

| Impingement + acromioclavicular disease + adhesive capsulitis | 4 (3%) |

| Impingement + acromioclavicular disease | 1 (1%) |

| Referred pain only | 2 (2%) |

| No diagnosis | 6 (5%) |

| Total | 131 (100%) |

In the study sample, the SPADI pain and disability subscales were observed to have a very good level of internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.81 and 0.90, respectively). The mean disability subscale score was 45 (95% CI 41–50) and the mean pain score was 58 (95% CI 54–62) with a total SPADI of 52 (95% CI 48–55) (maximum score 100) [10].

Our sample was compared with the norms on all the domains of the SF-36 and the differences in means were calculated, weighting the sample to compensate for age differences (Table 4). This showed a difference over all age groups between the HSE sample and our sample which was significant in six of the eight domains, being particularly marked for emotional role in addition to physical function and physical role. In the domains of general health and mental health the difference between the samples was not significant. We also compared the difference in different age groups and showed that shoulder pain has a greater effect on quality of life in the younger age groups, particularly in the way people can perform their physical, social and emotional roles within society. The unsigned partial correlation coefficient, adjusting for age, between the SPADI index and the SF-36 physical function was 0.41 (95% CI 0.24–0.55); and with SF-36 bodily pain was 0.57 (95% CI 0.43–0.68).

| SF-36 domaina . | Observed mean score . | Normativeb mean score . | Difference in means (95% CI) . | t-test P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 65 | 76 | −9.1 (−13.1 to −5.0) | <0.001 |

| Physical role | 37 | 75 | −37.6 (−44.6 to −30.7) | <0.001 |

| Bodily pain | 37 | 74 | −37.7 (−40.9 to −34.4) | <0.001 |

| General health | 66 | 67 | −0.8 (−4.5 to +2.9) | 0.67 |

| Vitality | 53 | 62 | −8.6 (−12.5 to −4.6) | <0.001 |

| Social role | 76 | 84 | −8.0 (−12.6 to −3.4) | <0.001 |

| Emotional role | 58 | 83 | −23.4 (−31.1 to −15.6) | <0.001 |

| Mental health | 73 | 76 | −3.2 (−6.7 to +0.2) | 0.07 |

| SF-36 domaina . | Observed mean score . | Normativeb mean score . | Difference in means (95% CI) . | t-test P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 65 | 76 | −9.1 (−13.1 to −5.0) | <0.001 |

| Physical role | 37 | 75 | −37.6 (−44.6 to −30.7) | <0.001 |

| Bodily pain | 37 | 74 | −37.7 (−40.9 to −34.4) | <0.001 |

| General health | 66 | 67 | −0.8 (−4.5 to +2.9) | 0.67 |

| Vitality | 53 | 62 | −8.6 (−12.5 to −4.6) | <0.001 |

| Social role | 76 | 84 | −8.0 (−12.6 to −3.4) | <0.001 |

| Emotional role | 58 | 83 | −23.4 (−31.1 to −15.6) | <0.001 |

| Mental health | 73 | 76 | −3.2 (−6.7 to +0.2) | 0.07 |

a123 subjects provided complete data for all SF-36 domains.

bThe normative score is obtained by applying the age-specific mean scores from the HSE to the age distribution in the study: 18–44 (n = 28), 45–54 (n = 21), 55–64 (n = 37), 65–74 (n = 24), 75+ (n = 13).

| SF-36 domaina . | Observed mean score . | Normativeb mean score . | Difference in means (95% CI) . | t-test P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 65 | 76 | −9.1 (−13.1 to −5.0) | <0.001 |

| Physical role | 37 | 75 | −37.6 (−44.6 to −30.7) | <0.001 |

| Bodily pain | 37 | 74 | −37.7 (−40.9 to −34.4) | <0.001 |

| General health | 66 | 67 | −0.8 (−4.5 to +2.9) | 0.67 |

| Vitality | 53 | 62 | −8.6 (−12.5 to −4.6) | <0.001 |

| Social role | 76 | 84 | −8.0 (−12.6 to −3.4) | <0.001 |

| Emotional role | 58 | 83 | −23.4 (−31.1 to −15.6) | <0.001 |

| Mental health | 73 | 76 | −3.2 (−6.7 to +0.2) | 0.07 |

| SF-36 domaina . | Observed mean score . | Normativeb mean score . | Difference in means (95% CI) . | t-test P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 65 | 76 | −9.1 (−13.1 to −5.0) | <0.001 |

| Physical role | 37 | 75 | −37.6 (−44.6 to −30.7) | <0.001 |

| Bodily pain | 37 | 74 | −37.7 (−40.9 to −34.4) | <0.001 |

| General health | 66 | 67 | −0.8 (−4.5 to +2.9) | 0.67 |

| Vitality | 53 | 62 | −8.6 (−12.5 to −4.6) | <0.001 |

| Social role | 76 | 84 | −8.0 (−12.6 to −3.4) | <0.001 |

| Emotional role | 58 | 83 | −23.4 (−31.1 to −15.6) | <0.001 |

| Mental health | 73 | 76 | −3.2 (−6.7 to +0.2) | 0.07 |

a123 subjects provided complete data for all SF-36 domains.

bThe normative score is obtained by applying the age-specific mean scores from the HSE to the age distribution in the study: 18–44 (n = 28), 45–54 (n = 21), 55–64 (n = 37), 65–74 (n = 24), 75+ (n = 13).

The large difference between study subjects and the HSE was not accounted for by past medical history. Cases with a significant past medical history did not differ from those without a past history by more than a mean of 5 points on any subscale.

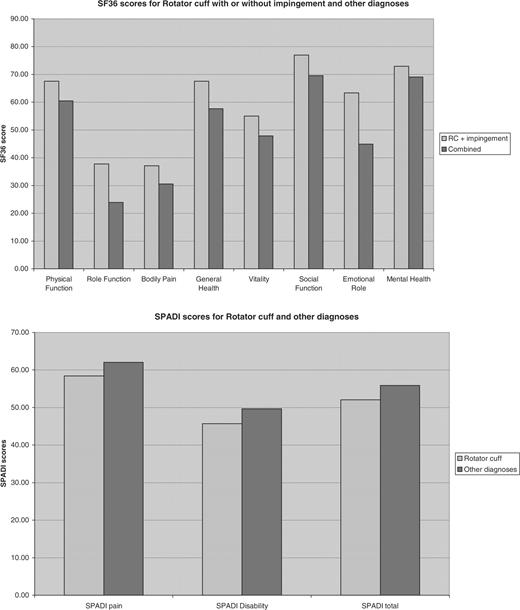

As the majority of patients had been given more than one diagnosis the impact of individual conditions on the SPADI and SF-36 could not be estimated accurately due to the confounding effects of a combined diagnosis. The SPADI and SF-36 scores, however, showed no significant difference depending upon the diagnosis using two broad categories (tendinosis with or without impingement or a combined group including ACJ, adhesive capsulitis, referred pain with or without tendinosis and/or impingement) (Table 5, Fig. 1).

(a) SF-36 scores for diagnosis of rotator cuff with or without impingement and other diagnoses

| . | Rotator cuff . | Other diagnoses . | Difference in means . | t-test P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 67.91 | 63.4 | 4.51 | 0.44 |

| Role function | 38.46 | 29 | 9.46 | 0.28 |

| Bodily pain | 37.16 | 32.52 | 4.64 | 0.30 |

| General health | 67.75 | 60.28 | 7.47 | 0.18 |

| Vitality | 54.95 | 49.6 | 5.35 | 0.33 |

| Social function | 77.20 | 71.5 | 5.70 | 0.28 |

| Emotional role | 63.74 | 46.67 | 17.07 | 0.09 |

| Mental health | 73.05 | 69.44 | 3.61 | 0.44 |

| . | Rotator cuff . | Other diagnoses . | Difference in means . | t-test P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 67.91 | 63.4 | 4.51 | 0.44 |

| Role function | 38.46 | 29 | 9.46 | 0.28 |

| Bodily pain | 37.16 | 32.52 | 4.64 | 0.30 |

| General health | 67.75 | 60.28 | 7.47 | 0.18 |

| Vitality | 54.95 | 49.6 | 5.35 | 0.33 |

| Social function | 77.20 | 71.5 | 5.70 | 0.28 |

| Emotional role | 63.74 | 46.67 | 17.07 | 0.09 |

| Mental health | 73.05 | 69.44 | 3.61 | 0.44 |

(a) SF-36 scores for diagnosis of rotator cuff with or without impingement and other diagnoses

| . | Rotator cuff . | Other diagnoses . | Difference in means . | t-test P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 67.91 | 63.4 | 4.51 | 0.44 |

| Role function | 38.46 | 29 | 9.46 | 0.28 |

| Bodily pain | 37.16 | 32.52 | 4.64 | 0.30 |

| General health | 67.75 | 60.28 | 7.47 | 0.18 |

| Vitality | 54.95 | 49.6 | 5.35 | 0.33 |

| Social function | 77.20 | 71.5 | 5.70 | 0.28 |

| Emotional role | 63.74 | 46.67 | 17.07 | 0.09 |

| Mental health | 73.05 | 69.44 | 3.61 | 0.44 |

| . | Rotator cuff . | Other diagnoses . | Difference in means . | t-test P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 67.91 | 63.4 | 4.51 | 0.44 |

| Role function | 38.46 | 29 | 9.46 | 0.28 |

| Bodily pain | 37.16 | 32.52 | 4.64 | 0.30 |

| General health | 67.75 | 60.28 | 7.47 | 0.18 |

| Vitality | 54.95 | 49.6 | 5.35 | 0.33 |

| Social function | 77.20 | 71.5 | 5.70 | 0.28 |

| Emotional role | 63.74 | 46.67 | 17.07 | 0.09 |

| Mental health | 73.05 | 69.44 | 3.61 | 0.44 |

(b) SPADI scores for diagnosis of rotator cuff with or without impingement and other diagnoses

| . | Rotator cuff . | Other diagnoses . | Difference in means . | t-test P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPADI pain | 58.44 | 62.04 | −3.60 | 0.43 |

| SPADI disability | 45.71 | 49.675 | −3.97 | 0.49 |

| SPADI total | 52.08 | 55.8575 | −3.78 | 0.44 |

| . | Rotator cuff . | Other diagnoses . | Difference in means . | t-test P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPADI pain | 58.44 | 62.04 | −3.60 | 0.43 |

| SPADI disability | 45.71 | 49.675 | −3.97 | 0.49 |

| SPADI total | 52.08 | 55.8575 | −3.78 | 0.44 |

(b) SPADI scores for diagnosis of rotator cuff with or without impingement and other diagnoses

| . | Rotator cuff . | Other diagnoses . | Difference in means . | t-test P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPADI pain | 58.44 | 62.04 | −3.60 | 0.43 |

| SPADI disability | 45.71 | 49.675 | −3.97 | 0.49 |

| SPADI total | 52.08 | 55.8575 | −3.78 | 0.44 |

| . | Rotator cuff . | Other diagnoses . | Difference in means . | t-test P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPADI pain | 58.44 | 62.04 | −3.60 | 0.43 |

| SPADI disability | 45.71 | 49.675 | −3.97 | 0.49 |

| SPADI total | 52.08 | 55.8575 | −3.78 | 0.44 |

Comparison of SPADI and SF-36 scores for patients with rotator cuff disease and other shoulder disorders.

Eighty eight per cent of patients in this study complained of sleep disturbance as a consequence of their shoulder pain.

Discussion

This study undertaken in primary care follows work performed previously by Vecchio et al. [18] showing the prevalence and spectrum of shoulder disease in the community. The incidence of shoulder pain we found is comparable with that obtained in previous studies [19, 20] although a higher incidence has been found elsewhere [21]. Nevertheless, pain in the shoulder region, regardless of aetiology, is associated with significant morbidity.

With age the frequency of musculoskeletal disorders increases; the prevalence of disability has been estimated to be as high as 50% in those aged 75 or over [1, 22–24]. Functional impairment of the shoulder at initial presentation has also been found to be associated with poorer long-term outcome [25].

Our sample represents a true cross-section of shoulder pain in society as we enrolled any patient with shoulder pain regardless of possible aetiology. As a consequence patients may have been included where the symptoms were not directly originating from shoulder pathology.

Difficulty with case definition [26] and lack of an adequate classification system plagues shoulder research. In the face of the lack of a universally accepted approach to clinical evaluation of the shoulder, we used widely accepted clinical tests for specific disorders that are commonly used in clinical practice. We have shown that several of these tests are reproducible between observers [27]. The validity of tests for shoulder pain, however, remains unclear and research efforts focused on this pivotal issue are required. Given the weakness of classification, this study has utilized those case definitions which have been tested by us and other groups and therefore represent the currently accepted standard for the study of various clinical shoulder disorders.

The median time taken for our patients to seek medical advice was 10 weeks. It would appear that many people are willing to accept pain and disability at least in the short to medium term before presenting for an opinion. Two previous studies and a survey have shown that the elderly do indeed suffer from significant pathology and disability and that it is under-recognized [28–31]. Many accept their symptoms as an inevitable part of getting older. Most resultant disabilities were reflected in activities such as bathing, dressing and toileting. This was reflected in our study with the most problematic areas being placing objects on a high shelf, washing one's back and carrying heavy objects.

It is apparent that one cannot rely on simple outcome measures for shoulder assessment. Range of movement (ROM) as a measure is inadequate as the majority of people in the community with self-reported shoulder pain do not have widespread restriction of movement [32]. Pain scores alone are also inadequate to assess the severity of shoulder disease and impairment [19, 33].

We utilized the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI), a disease-specific index, to ascertain how shoulder pain affects an individual in primary care. Internal consistency was observed to be very good in this cohort. Its main weakness is the omission of questions pertaining to pain interfering with sleep, which was found to be one of the most common problems in these patients [5, 10, 33]. A question on sleep disturbance was included in our study and was also found to be an extremely common problem (88%). SPADI scores were high in our patients and are similar to those obtained when used in a similar setting [10].

The SF-36 health survey was used to ascertain the general health of patients with shoulder pain. The SF-36 health survey has been validated and may be suitable as an outcome measure for routine use within the National Health Service (NHS) [34–37]. There is some evidence that the SF-36 may be more sensitive than the modified Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) at detecting disability associated with shoulder disorders [1]. The great majority of patients scored lower than healthy norms and equivalent to patients with other medical conditions as has been shown previously [38, 39]. This is an interesting finding as none of the health status parameters of the SF-36 directly assesses shoulder function. Most astounding is that shoulder disease ranked in severity with conditions such as congestive cardiac failure, acute myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus and clinical depression. These patients, however, had well-defined shoulder conditions and had been assessed in an orthopaedic clinic [39]. It is important to remember, however, that the prognosis of shoulder disorders is favourable compared with life-threatening illnesses such as cardiac failure, and the impact on general health may be much less if expressed in terms of quality-adjusted life years or disability-adjusted life years. Although our patients presented with shoulder disorders their overall poor general health status may not entirely be a consequence of this.

Badcock et al. [33] highlighted the importance of a disability measure as patients’ psychological health was related to pain only by its association with disability. We did not specifically look at this issue; however, this is of paramount importance as psychological well-being has a large impact on the general well-being of individuals.

Generic health questionnaires, such as the SF-36, are generally insensitive to specific disorders and therefore need to be combined with specific questionnaires, e.g. SPADI. The age-adjusted correlation between the SPADI and the domains of the SF-36 relating to pain were significantly lower than 0.7, indicating that the general SF-36 and the specific SPADI measures each explain less than 50% of the variability in responses recorded in the other measure. By using these two measures, comparisons can be made between different conditions as to the effectiveness of intervention upon the illness. It is imperative that this model be used in order to address medical illnesses that have the greatest impact on patients in order to tailor appropriate therapy. Furthermore, as resource allocation is limited, comparisons must be made between medical conditions in order to budget accordingly. This could be made possible by use of generic health measures.

A further difficulty of the classification systems and diagnostic criteria we employed and which is generally used in shoulder research is the lack of mutual exclusiveness. This is a problem with not only the diagnostic criteria but also with the underlying pathology. For example, it is challenging to assess any other pathology of the shoulder in the presence of adhesive capsulitis.

Clinics held in the community may be one of the best ways to maximize health-care allocation. In a study we have undertaken [27] delegation of assessment of shoulder pain to allied health staff, including nurses, may be possible. Many conditions can therefore be dealt with in primary care thereby reducing the out-patient waiting list. Van der Windt et al. [40] found that only 10% of patients who presented to general practice with shoulder pain were referred for specialist opinion. Patients who cannot be easily assessed or those who re-present could then be referred for specialist opinion.

Conclusion

Our study, conducted in primary care, suggests that shoulder pain is associated with significantly reduced health when measured by both shoulder-specific and generic means. The most frequent diagnoses were lesions of the rotator cuff with or without signs of impingement. Management should focus on prevention and early intervention in these complaints.

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

Urwin M, Symmons D, Allison T et al. Estimating the burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the community: the comparative prevalence of symptoms at different anatomical sites, and the relation to social deprivation.

Nygren A, Berlund A, von Koch M. Neck-and-shoulder pain, an increasing problem. Strategies for using health insurance to follow trends.

Cyriax J.

Palmer K, Walker-Bone K, Linaker C et al. The Southampton examination schedule for the diagnosis of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb.

Roach KE, Budiman-Mak E, Songsiridej N, Lerthratanakul Y. Development of a shoulder pain and disability index.

Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M.

Calis M, Akgun K, Birtane M, Karacan I, Calis H, Tuzun F. Diagnostic values of clinical diagnostic tests in subacromial impingement syndrome.

Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia: report of the multicentre criteria committee.

Williams JW, Holleman JR, Simel DL. Measuring shoulder function with the shoulder pain and disability index.

Prescott-Clarke P, Primatesta P (eds).

Bowling A, Bond M, Jenkinson C, Lamping D. Short form 36 (SF-36) health survey questionnaire: which normative data should be used? Comparisons between the norms provided by the Omnibus Survey in Britain, The Health Survey for England and the Oxford Healthy Life Survey.

Jenkinson C, Layte R, Wright L,

Dobson AJ, Kuulasmaa K, Eberle E, Scherer J. Confidence intervals for weighted sums of Poisson parameters.

Vecchio P, Kavanagh RT, Hazleman BL, King RH. Shoulder pain in a community-based rheumatology clinic.

Mäkelä M, Heliövaara M, Sainio P, Knekt P, Impivaara O, Aromaa A. Shoulder joint impairment among Finns aged 30 years or over: prevalence, risk factors and co-morbidity.

Croft P. Soft tissue rheumatism. In: Silman AJ, Hochberg MC, eds.

Lamberts H, Brouwer HJ, Mohrs J.

Pope DP, Croft PR, Pritchard CM, Silman AJ. Prevalence of shoulder pain in the community: the influence of case definition.

Badley EM, Tennant A. Changing profile of joint disorders with age: findings from a postal survey of the population of Calderdale, West Yorkshire, United Kingdom.

Martin J, Meltzer H, Elliot D.

Bartolozzi A, Andreychik D, Ahmad S. Determinants of outcomes in the treatment of rotator cuff disease.

Buchbinder R, Goel V, Bombardier C, Hogg-Johnson S. Classification systems of soft tissue disorders of the neck and upper limb: do they satisfy methodological guidelines?

Ostor AJ, Richards CA, Provost TA, Hazleman BL, Speed CA. Inter rater reliability of clinical tests for rotator cuff lesions.

Office of Population Census and Surveys (OPCS), The Royal College of General Practitioners, Department of Health and Social Security.

Chakravarty KK, Webley M. Disorders of the shoulder: an often unrecognised cause of disability in elderly people.

Chard MD, Hazleman BL. Shoulder disorders in the elderly (a hospital study).

Hasvold T, Johnsen R. Headache and neck or shoulder pain—frequent and disabling complaints in the general population.

Pope DP, Croft PR, Pritchard CM, Macfarlane GJ, Silman AJ. The frequency of restricted range of movement in individuals with self-reported shoulder pain: results from a population-based survey.

Badcock LJ, Lewis M, Hay EM, McCarney R, Croft PR. Chronic shoulder pain in the community: a syndrome of disability or distress?

Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NMB et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care.

Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Wright L. The short form 36 (SF-36) health survey questionnaire: normative data for adults of working age.

Garrat AM, Ruta DA, Abdalla MI, Buckingham KJ, Russell IT. The SF-36 health survey questionnaire: an outcome measure suitable for routine use within the NHS?

Lyons RA, Perry HM, Littlepage BNC. Evidence for the validity of the short form 36 questionnaire (SF-36) in an elderly population.

Lyons RA, Lo SV, Littlepage BNC. Comparative health status of patients with 11 common illnesses in Wales.

Gartsman GM, Brinker MR, Khan M, Karahan M. Self-assessment of general health status in patients with five common shoulder conditions.

Author notes

Rheumatology Research Unit, Box 194, Addenbrooke's Hospital, Hills Rd, Cambridge CB2 2QQ and 1Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Institute of Public Health, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 2QQ, UK.

- consultation

- emotions

- adhesive capsulitis

- demography

- early intervention (education)

- health status

- health surveys

- pain

- physicians, family

- primary health care

- rheumatology

- shoulder pain

- diagnosis

- shoulder region

- acromioclavicular joint

- pain, referred

- disability

- rotator cuff tendinitis

- pain score

- sf-36

- physical function

- prevention

- shoulder disorders

Comments