Abstract

Summary

Application of the WHO fracture prediction algorithm in conjunction with an updated US economic analysis indicates that osteoporosis treatment is cost-effective in patients with fragility fractures or osteoporosis, in older individuals at average risk and in younger persons with additional clinical risk factors for fracture, supporting existing practice recommendations.

Introduction

The new WHO fracture prediction algorithm was combined with an updated economic analysis to evaluate existing NOF guidance for osteoporosis prevention and treatment.

Methods

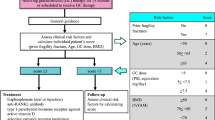

The WHO fracture prediction algorithm was calibrated to the US population using national age-, sex- and race-specific death rates and age- and sex-specific hip fracture incidence rates from the largely white population of Olmsted County, MN. Fracture incidence for other races was estimated by ratios to white women and men. The WHO algorithm estimated the probability (%) of a hip fracture (or a major osteoporotic fracture) over 10 years, given specific age, gender, race and clinical profiles. The updated economic model suggested that osteoporosis treatment was cost-effective when the 10-year probability of hip fracture reached 3%.

Results

It is cost-effective to treat patients with a fragility fracture and those with osteoporosis by WHO criteria, as well as older individuals at average risk and osteopenic patients with additional risk factors. However, the estimated 10-year fracture probability was lower in men and nonwhite women compared to postmenopausal white women.

Conclusions

This analysis generally endorsed existing clinical practice recommendations, but specific treatment decisions must be individualized. An estimate of the patient’s 10-year fracture risk should facilitate shared decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

NOF (2005) National Osteoporosis Foundation: Physician Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. www.nof.org/physguide/index.htm

Kanis JA, Melton LJ III, Christiansen C et al (1994) The diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 9:1137–1141

Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C et al (2004) A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone 35:375–382

U. S. Preventive Services Task Force (2002) Screening for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med 137:526–528

Eddy D, Johnston CC, Cummings SR et al (1998) Osteoporosis: review of the evidence for prevention, diagnosis and treatment and cost-effectiveness analysis. Osteoporos Int 8 Suppl 4:S7–80

Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL et al (2002) Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288:321–333

Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR et al (2004) Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial.[see comment]. JAMA 291:1701–1712

Rosen CJ (2005) Clinical practice. Postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 353:595–603

U.S.D.H.H.S. (2004) Chapter 4. The Frequency of Bone Disease. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD, pp 69–87

Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH et al (2007) Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res 22:465–475

Börgstrom F, Johnell O, Kanis JA et al (2006) At what hip fracture risk is it cost-effective to treat? International intervention thresholds for the treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 17:1459–1471

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A et al. (2008) FRAX™ and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int DOI 10.1007/s00198-007-0543-5

Tosteson AN (2008) Cost-effective osteoporosis treatment thresholds: the United States perspective. Osteoporos Int DOI 10.1007/s00198-007-0550-6

Murphy DJ, Gahm GJ, Santilli S et al (2002) Seniors’ preferences for cancer screening and medication use based on absolute risk reduction. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 57A:M100–105

Leslie WD, Siminoski K, Brown JP (2007) Comparative effects of densitometric and absolute fracture risk classification systems on projected intervention rates in postmenopausal women. J Clin Densitom 10:124–131

Bonjour P, Clark P, Cooper C et al. (2007) Assessment of Osteoporosis at the Primary Care Level. WHO Technical Report Series. WHO, Geneva

Oden A, Dawson A, Dere W et al (1998) Lifetime risk of hip fracture is underestimated. Osteoporos Int 8:599–603

Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL et al (1998) Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int 8:468–489

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O et al (2007) The use of clinical risk factors enhances the performance of BMD in the prediction of hip and osteoporotic fractures in men and women. Osteoporos Int 18:1033–1046

Arias E, Anderson RN, Kung HC et al (2003) Deaths: final data for 2001. Natl Vital Stat Rep 52:1–115

Melton LJ III, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM (1999) Fracture incidence in Olmsted County, Minnesota: Comparison of urban with rural rates and changes in urban rates over time. Osteoporos Int 9:29–37

Arneson TJ, Melton LJ III, Lewallen DG et al (1988) Epidemiology of diaphyseal and distal femoral fractures in Rochester, Minnesota, 1965–1984. Clin Orthop 234:188–194

Bauer RL (1988) Ethnic differences in hip fracture: a reduced incidence in Mexican Americans. Am J Epidemiol 127:145–149

Silverman SL, Madison RE (1988) Decreased incidence of hip fracture in Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: California Hospital Discharge Data. Am J Public Health 78:1482–1483

Jacobsen SJ, Goldberg J, Miles TP et al (1990) Hip fracture incidence among the old and very old: a population-based study of 745,435 cases. Am J Public Health 80:871–873

Griffin MR, Ray WA, Fought RL et al (1992) Black-white differences in fracture rates. Am J Epidemiol 136:1378–1385

Baron JA, Barrett J, Malenka D et al (1994) Racial differences in fracture risk. Epidemiology 5:42–47

Baron JA, Karagas M, Barrett J et al (1996) Basic epidemiology of fractures of the upper and lower limb among Americans over 65 years of age. Epidemiology 7:612–618

Zingmond DS, Melton LJ 3rd, Silverman SL (2004) Increasing hip fracture incidence in California Hispanics, 1983 to 2000. Osteoporos Int 15:603–610

Lauderdale DS, Jacobsen SJ, Furner SE et al (1998) Hip fracture incidence among elderly Hispanics. Am J Public Health 88:1245–1247

Lauderdale DS, Jacobsen SJ, Furner SE et al (1997) Hip fracture incidence among elderly Asian-American populations. Am J Epidemiol 146:502–509

Cummings SR, Melton LJ (2002) Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 359:1761–1767

Kanis JA, Borgstrom F, De Laet C et al (2005) Assessment of fracture risk. Osteoporos Int 16:581–589

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL et al (2002) Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA 288:1723–1728

Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Carroll MD et al (2004) Mean body weight, height, and body mass index, United States 1960–2002. Adv Data 347:1–17

Kanis JA, Black D, Cooper C et al (2002) A new approach to the development of assessment guidelines for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 13:527–536

Delmas PD, Rizzoli R, Cooper C et al (2005) Treatment of patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis is worthwhile. The position of the International Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporos Int 16:1–5

Lewiecki EM (2005) Review of guidelines for bone mineral density testing and treatment of osteoporosis. Curr Osteoporos Rep 3:75–83

Kanis JA, Borgstrom F, Zethraeus N et al (2005) Intervention thresholds for osteoporosis in the UK. Bone 36:22–32

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A et al (2005) Intervention thresholds for osteoporosis in men and women: a study based on data from Sweden. Osteoporos Int 16:6–14

Cummings SR (2006) A 55-year-old woman with osteopenia. JAMA 296:2601–2610

Khosla S, Melton LJ III (2007) Osteopenia. N Engl J Med 356:2293–2300

Siris ES, Chen YT, Abbott TA et al (2004) Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med 164:1108–1112

Pasco JA, Seeman E, Henry MJ et al (2006) The population burden of fractures originates in women with osteopenia, not osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 17:1404–1409

Sanders KM, Nicholson GC, Watts JJ et al (2006) Half the burden of fragility fractures in the community occur in women without osteoporosis. When is fracture prevention cost-effective? Bone 38:694–700

Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE et al (1998) Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA 280:2077–2082

De Laet C, Oden A, Johansson H et al (2005) The impact of the use of multiple risk indicators for fracture on case-finding strategies: a mathematical approach. Osteoporos Int 16:313–318

Schousboe JT, Ensrud KE, Nyman JA et al (2005) Universal bone densitometry screening combined with alendronate therapy for those diagnosed with osteoporosis is highly cost-effective for elderly women. J Am Geriatr Soc 53:1697–1704

Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A et al (2004) A meta-analysis of prior corticosteroid use and fracture risk. J Bone Miner Res 19:893–899

Anonymous (2001) Recommendations for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: 2001 update. American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheum 44:1496–1503

U.S.D.H.H.S. (2004) Chapter 3. Diseases of Bone. In Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General, Rockville, MD, pp 41–65

Alam NM, Archer JA, Lee E (2004) Osteoporotic fragility fractures in African Americans: under-recognized and undertreated. J Natl Med Assoc 96:1640–1645

Farley JF, Cline RR, Gupta K (2006) Racial variations in antiresorptive medication use: results from the 2000 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). Osteoporos Int 17:395–404

Melton LJ III, Marquez MA, Achenbach SJ et al (2002) Variations in bone density among persons of African heritage. Osteoporos Int 13:551–559

Barrett-Connor E, Siris ES, Wehren LE et al (2005) Osteoporosis and fracture risk in women of different ethnic groups. J Bone Miner Res 20:185–194

Cauley JA, Lui LY, Ensrud KE et al (2005) Bone mineral density and the risk of incident nonspinal fractures in black and white women. JAMA 293:2102–2108

Hanlon JT, Landerman LR, Fillenbaum GG et al (2002) Falls in African American and white community-dwelling elderly residents. J Gerontol: Med Sci 57A:M473–478

Melton LJ III, Cooper C (2001) Magnitude and impact of osteoporosis and fractures. In: Marcus R, Feldman D, Kelsey J (eds) Osteoporosis. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 557–567

Stafford RS, Drieling RL, Hersh AL (2004) National trends in osteoporosis visits and osteoporosis treatment, 1988–2003. Arch Intern Med 164:1525–1530

Kanis JA (2002) Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk. Lancet 359:1929–1936

Schousboe JT, Nyman JA, Kane RL et al (2005) Cost-effectiveness of alendronate therapy for osteopenic postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med 142:734–741

Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch ER, Jamal SA et al (2004) Practice patterns in the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis after a fragility fracture: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 15:767–778

Browner WS (2007) Predicting fracture risk: tougher than it looks. BoneKEy 4:226–230

Ettinger B, Hillier TA, Pressman A et al (2005) Simple computer model for calculating and reporting 5-year osteoporotic fracture risk in postmenopausal women. J Women’s Health 14:159–171

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank David C. Radley and Loretta H. Pearson for research assistance and Mary G. Roberts for help in preparing the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors comprise the National Osteoporosis Foundation Guide Committee.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dawson-Hughes, B., Tosteson, A.N.A., Melton, L.J. et al. Implications of absolute fracture risk assessment for osteoporosis practice guidelines in the USA. Osteoporos Int 19, 449–458 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-008-0559-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-008-0559-5