Abstract

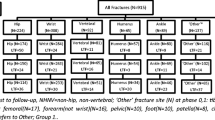

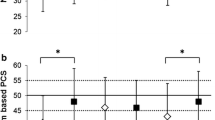

Osteoporotic fractures can be a major cause of morbidity. It is important to determine the impact of fractures on health-related quality of life (HRQL). A total of 3,394 women and 1,122 men 50 years of age and older, who were recruited for the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos), participated in this cross-sectional study. Minimal trauma fractures of the hip, pelvis, spine, lower body (included upper and lower leg, knee, ankle, and foot), upper body (included arm, elbow, sternum, shoulder, and clavicle), wrist and hand (included forearm, hand, and finger), and ribs were studied. Participants with subclinical vertebral deformities were also examined. The Health Utilities Index Mark II and III Systems were used to assess HRQL. Past osteoporotic fractures varied in prevalence from 1.2% (pelvis) to 27.8% (lower body) in women and 0.3% (pelvis) to 29.3% (wrist) in men. Multivariate linear regression analyses [parameter estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI)] indicated that minimal trauma fractures were negatively associated with HRQL and that this relationship depends on fracture type and gender. The multi-attribute scores for the Mark II system were negatively related to hip (−0.05; 95% CI: −0.09, −0.01), lower body (−0.02; 95% CI: −0.03, −0.000), and subclinical vertebral fractures (−0.02; 95% CI: −0.03, −0.00) for women. The multi-attribute scores for the Mark III system were negatively related to hip (−0.09; 95% CI: −0.14, −0.03) and rib fractures (−0.06; 95% CI: −0.11, −0.00) for women, and rib fractures (−0.06; 95% CI: −0.12, −0.00) for men. In conclusion, this study demonstrates a negative association between osteoporotic fractures and quality of life in both women and men.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Jones G, Nguyen T, Sambrook PN, et al (1994) Symptomatic fracture incidence in elderly men and women: The Dubbo osteoporosis epidemiologic study (DOES). Osteoporos Int 4:277–282

Kannue P, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Palvanen M, Vuori I, Jarvinen M (1999) Hip fractures in Finland between 1970 and 1997 and predictions for the future. Lancet 353:802–805

Melton LJ III (1995) Epidemiology of fractures. In: Riggs BL, and Melton LJ III (eds) Osteoporosis: etiology, diagnosis and management, 2nd edn, Raven, New York, pp 225–247

Lips P (1997) Epidemiology and predictors of fractures associated with osteoporosis. Am J Med 103:3S-11S

Melton LJ III, Chrischilles EA, Cooper C, Lane AW, Riggs BL (1992) Perspective. How many women have osteoporosis? J Bone Miner Res 7:1005–1010

Bengner U, Johnell O, Redlund-Johnell I (1986) Increasing incidence of tibia condyle and patella fractures. Acta Orthop Scand 57:2297–2304

Luthje P, Nurmi I, Kataja M, Heliovaara M, Santavirta Santavirta S (1995) Incidence of pelvic fractures in Finland in 1988. Acta Orthop Scand 66:245–248

Rose SH, Melton LJ, Morrey BF, Ilstrup DM, Riggs BL (1982) Epidemiologic features of humeral fractures. Clin Orthop 168:24–30

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, Jonsson B, de Laet C, Dawson A (2001) The burden of osteoporotic fractures: a method for setting intervention thresholds. Osteoporos Int 12:417–427

Nguyen TV, Center JR, Sambrook PH, Eisman JA (2001) Risk factors for proximal humerus, forearm, and wrist fractures in elderly men and women. The Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study. Am J Epidemiol 153:587–595

Feeny DH, Torrance GW, Furlong WJ (1996) Health utilities index. In: Spilker B (ed) Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials, 2nd edn, Lippincott, Philadelphia pp 239–252

Osteoporosis quality of life study group (1997) Measuring quality of life in women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 7:478–487

Randell AG, Bhalerao N, Nguyen T, et al (1998) Quality of life in osteoporosis: reliability, consistency, and validity of the osteoporosis assessment questionnaire. J Rheumatol 25:1171–1179

Lips P, Cooper C, Agnusdei D, et al (1997) Quality of life as outcome in the treatment of osteoporosis; the development of a questionnaire for quality of life by the European Foundation for Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 7:36–38

Chandler JM, Martin AR, Girman C, et al (1998) Reliability of an osteoporosis-targeted quality of life survey instrument for use in the community: OPTQol. Osteoporos Int 8:127–135

Melton LJ III (1999) Cost-effective treatment strategies for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 9[Suppl 2]:111–116

Tosteson ANA (1997) Quality of life in the economic evaluation of osteoporosis prevention and treatment. Spine 22(24S):58–62

Kreiger N, Tenenhouse A, Joseph L, et al (1999) The Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos); background, rationale, methods. Can J Aging 18:376–387

Torrance GW, W Furlong, Feeny D, Boyle MH (1995) Multi-attribute preference functions: health utilities index. Pharmacoeconomics 7:503–520

S.A. Jackson, A. Tenenhouse, L. Robertson and the CaMos Study Group (2000) Vertebral fractures definition from population-based data: preliminary results from the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos). Osteoporosis Int 11:680–687

Kass RE, Raftery AE (1995) Bayes factores. J Am Stat Assoc 90:773–795

Chrischilles EA, Shireman T, Wallace R (1994) Costs and health effects of osteoporotic fractures. Bone 15:377–386

Kanis JA, Geusens P, Christiansen C, et al (1991) Guidelines of clinical trials in osteoporosis. A position paper of the European foundation for osteoporosis and bone disease. Osteoporos Int 1:182–188

Reginster JY, Compston JE, Jones EA et al (1995) Recommendations for the registration of new chemical entities used in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int 57:247–250

Cooper C (1997) The crippling consequences of fractures and their impact on quality of life. Am J Med 103:12S–19S

Eastell R, Reid Dm, Compston J, et al (2001) Secondary prevention of osteoporosis: when should a non-vertebral fracture be a trigger for action? Q J Med 94:575–597

Melton LJ III, Sampson JM, Morrey B F, Ilstrup DM (1981) Epidemiologic features of pelvic fractures. Clin Orthop 155:43–47

Gold DT (1996) The clinical impact of vertebral fractures: quality of life in women with osteoporosis. Bone 18:185S–189S

de Bruijn HP (1987) Functional treatment of colles fracture. Acta Orthop Scand 223[Suppl]:1–95

Kaukonen JP, Karaharju EO, Porras M, et al (1988) Functional recovery after fractures of the distal forearm: analysis of radiographic and other factors affecting the outcome. Ann Chir Gynaecol 77:27–31

Greendale GA, Barrett-Connor E, Ingles S, Haile R (1995) Late physical and functional effects of osteoporotic fracture in women: The Rancho Bernardo Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 43:955–961

Ettinger B, Black DM, Nevitt MC, et al (1992) Contribution of vertebral deformities to chronic back pain and disability. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group 7:449–456

Riedinger MS, Dracup KA, Brecht ML, Padilla G, Sarna L, Ganz PA (2001) Quality of life in patients with heart failure: do gender differences exist? Heart Lung 30:105–116

Holbrook Tl, Hoyt DB, Anderson JP (2001) The importance of gender on outcome after major trauma: functional and psychologic outcomes in women versus men. J Trauma 50:270–273

Begerow B, Pfeifer M, Pospeschill M, et al (1999) Time since vertebral fracture: an important variable concerning quality of life in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 10:26–33

Cranney A, Coyle D, Pham BA, et al (2001) The psychometric properties of patient preferences in osteoporosis. J Rheumatol 28:132–137

Torrance GW, Zhang Y, Feeny DH, Furlong W, Barr RD (1992) Multi-attribute preference functions for a comprehensive health status classification system. Working paper #92–18, Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis Working Paper Series, McMaster University

Gabriel SE, Kneeland TS, Melton LJ III, Moncur MM, Ettinger B, Tosteson ANA (1999) Health-related quality of life in economic evaluations for osteoporosis: whose values should we use? Med Decis Making 19:141–148

Manuel DG, Schultz SE, Kopec JA (2002) Measuring the health burden of chronic disease and injury using health adjusted life expectancy and the health utilities index. J Epidemiol Community Health 56:843–845

Mittmann N, Trakas K, Risebrough N, Liu BA (1999) Utility scores for chronic conditions in a community-dwelling population. Pharmacoeconomics 15:369–376

Silverman S, Cranney A (1997) Quality of life measurements in osteoporosis. J Rheumatol 24:1218–1221

Tosteson ANA, Gabriel SE, Grove MR, Momcur MM, Kneeland TS, Melton LJ III (2001) Impact of hip and vertebral fractures on Quality-adjusted life years. Osteoporos Int 12:1042–1049

Dolan P, Torgerson D, Kakarlapudi TK (1999) Health-related quality of life of Colles' fracture patients. Osteoporos Int 9:196–199

Ivers RQ, Cumming RG, Mitchell P, Peduto AJ (2002) The accuracy of self-reported fractures in older people. J Clin Epidemiol 55:452–457

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the rest of the CaMoS Research Group, including: J Allan, L. Blondeau, B. Gardner-Bray, P. Hartman, J. Thingvold, S. Kirkland, N. Kreiger, P. Krutzen, S. Godmaire, E. Lejeune, B.C. Lentle, B. Matthews, N.Migneault-Roy, M. Parsons, R.S. Rittmaster, L. Robertson, B. Stanfield, and Y. Vigna.

L. Joseph is a senior scientist funded by CIHR. The CaMos was funded by the Senior's Independence Research Program through the National Health Research and Development Program of Health Canada (Project No. 6605-4003-OS). The Medical Research Council of Canada, MRC-PMAC Health Program, Merck Frosst Canada Inc., Eli Lilly Canada Inc., Procter and Gamble Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc., and the Dairy Farmers of Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study was conducted in conjunction with other members of the CaMOS Research Group.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adachi, J.D., Ioannidis, G., Pickard, L. et al. The association between osteoporotic fractures and health-related quality of life as measured by the Health Utilities Index in the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos). Osteoporos Int 14, 895–904 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-003-1483-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-003-1483-3