Abstract

Chronic low-grade inflammation was recognized during the past decade as an important risk factor for the development of atherosclerosis and, more recently, for the development of heart failure. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are at increased risk of morbidity and mortality from ischemic cardiovascular events and heart failure. Epidemiologic and clinical studies indicate that RA is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, which suggests that chronic exposure to high levels of inflammatory mediators contributes to this enhanced risk. The relative contribution of conventional risk factors to the acceleration of cardiovascular disease does not seem to be increased in patients with RA compared with control populations. Nonetheless, some preclinical laboratory measures of risk factors (e.g. insulin sensitivity) are adversely modulated in the context of the highly inflammatory rheumatoid microenvironment. Discerning the net effect of RA therapies on cardiovascular disease is also challenging because, theoretically, their biologic effects could either promote or attenuate atherosclerosis and ventricular dysfunction; however, available data suggest a beneficial effect on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with RA. This review provides an overview of the potential influence of RA and its treatment on the development and progression of cardiovascular disease, and outlines some preliminary recommendations for prevention and management of this complication in patients with RA.

Key Points

-

Individuals with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are at an increased risk of cardiovascular events, particularly ischemic heart disease and heart failure, and death from cardiovascular disease

-

An increased prevalence of atherosclerosis and myocardial dysfunction in patients with RA is only partially explained by conventional cardiovascular risk factors, suggesting that RA-related factors such as chronic high-grade systemic inflammation might be contributory

-

In the absence of evidence-based approaches (such as those provided by clinical trials) for the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease risk in patients with RA, aggressive control of both synovitis and conventional cardiovascular risk factors is advised in all patients

-

Treatment goals for conventional cardiovascular risk factors should center around an assessment of the 10-year coronary artery disease risk of individual patients with RA, with all patients assessed as at least intermediate risk

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ross R (1999) Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 340: 115–126

Vasan RS et al. (2003) Inflammatory markers and risk of heart failure in elderly subjects without prior myocardial infarction: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 107: 1486–1491

del Rincon ID et al. (2001) High incidence of cardiovascular events in a rheumatoid arthritis cohort not explained by traditional cardiac risk factors. Arthritis Rheum 44: 2737–2745

Watson DJ et al. (2003) All-cause mortality and vascular events among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, or no arthritis in the UK General Practice Research Database. J Rheumatol 30: 1196–1202

Wolfe F et al. (2003) Increase in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease prevalence in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 30: 36–40

Solomon DH et al. (2003) Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in women diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation 107: 1303–1307

Doran MF et al. (2002) Trends in incidence and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis in Rochester, Minnesota, over a forty-year period. Arthritis Rheum 46: 625–631

Wolfe F et al. (1994) The mortality of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 37: 481–494

Turesson C et al. (2004) Increased incidence of cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from a community-based study. Ann Rheum Dis 63: 952–955

Nicola PJ et al. (2005) The risk of congestive heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study over 46 years. Arthritis Rheum 52: 412–420

Maradit-Kremers H et al. (2005) Increased unrecognized coronary heart disease and sudden deaths in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 52: 402–411

Banks M et al. (2000) Rheumatoid arthritis is an independent risk factor for ischemic heart disease. Arthritis Rheum 43: S385

Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S et al. (2003) Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 48: 2741–2749

Chung CP et al. (2005) Increased coronary-artery atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis: relationship to disease duration and cardiovascular risk factors. Arthritis Rheum 52: 3045–3053

Gonzalez-Juanatey C et al. (2003) Increased prevalence of severe subclinical atherosclerotic findings in long-term treated rheumatoid arthritis patients without clinically evident atherosclerotic disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 82: 407–413

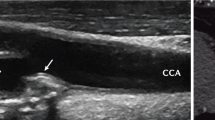

Park YB et al. (2002) Atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis: morphologic evidence obtained by carotid ultrasound. Arthritis Rheum 46: 1714–1719

Nagata-Sakurai M et al. (2003) Inflammation and bone resorption as independent factors of accelerated arterial wall thickening in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 48: 3061–3067

del Rincon I et al. (2005) Lower limb arterial incompressibility and obstruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 64: 425–432

Vaudo G et al. (2004) Endothelial dysfunction in young patients with rheumatoid arthritis and low disease activity. Ann Rheum Dis 63: 31–35

Giles JT et al. (2005) Myocardial dysfunction in rheumatoid arthritis: epidemiology and pathogenesis. Arthritis Res Ther 7: 195–207

Firestein GS (1999) Rheumatoid synovitis and pannus. In Rheumatology, edn 2, 13.1–13.24 (eds Klippel JH and Dieppe PA) London: Mosby

Stary HC et al. (1995) A definition of advanced types of atherosclerotic lesions and a histological classification of atherosclerosis. A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Circulation 92: 1355–1374

Uzui H et al. (2002) Increased expression of membrane type 3-matrix metalloproteinase in human atherosclerotic plaque: role of activated macrophages and inflammatory cytokines. Circulation 106: 3024–3030

Kato H et al. (2000) Complement mediated vascular endothelial injury in rheumatoid nodules: a histopathological and immunohistochemical study. J Rheumatol 27: 1839–1847

Ridker PM et al. (2000) C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med 342: 836–843

Kubota T et al. (2000) Expression of proinflammatory cytokines in the failing human heart: comparison of recent-onset and end-stage congestive heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant 19: 819–824

Bozkurt B et al. (1998) Pathophysiologically relevant concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-alpha promote progressive left ventricular dysfunction and remodeling in rats. Circulation 97: 1382–1391

Cathcart ES and Spodick DH (1962) Rheumatoid heart disease. A study of the incidence and nature of cardiac lesions in rheumatoid arthritis. J Med 266: 959–964

Klimiuk PA et al. (2003) Circulating tumour necrosis factor-α and soluble tumour necrosis factor receptors in patients with different patterns of rheumatoid synovitis. Ann Rheum Dis 62: 472–475

Dibbs Z et al. (1999) Natural variability of circulating levels of cytokines and cytokine receptors in patients with heart failure: implications for clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 33: 1935–1942

Maradit-Kremers H et al. (2005) Cardiovascular death in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum 52: 722–732

Navarro-Cano G et al. (2003) Association of mortality with disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis, independent of comorbidity. Arthritis Rheum 48: 2425–2433

Del Rincon I et al. (2003) Association between carotid atherosclerosis and markers of inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis patients and healthy subjects. Arthritis Rheum 48: 1833–1840

Padyukov L et al. (2004) A gene-environment interaction between smoking and shared epitope genes in HLA-DR provides a high risk of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 50: 3085–3092

Solomon DH et al. (2004) Cardiovascular risk factors in women with and without rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 50: 3444–3449

Dessein PH et al. (2002) Cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis versus osteoarthritis: acute phase response related decreased insulin sensitivity and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol as well as clustering of metabolic syndrome features in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res 4: R5

Park YB et al. (2002) Effects of antirheumatic therapy on serum lipid levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study. Am J Med 113: 188–193

Popa C et al. (2005) Influence of anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 64: 303–305

Boers M et al. (2003) Influence of glucocorticoids and disease activity on total and high density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 62: 842–845

Giles JT et al. (2005) Body composition in normal weight, overweight, and obese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 52: S331

Westhovens R et al. (1997) Body composition in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 36: 444–448

Katsuki A et al. (1998) Serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha are increased in obese patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83: 859–862

You T et al. (2005) Abdominal adipose tissue cytokine gene expression: relationship to obesity and metabolic risk factors. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 288: E741–E747

McEntegart A et al. (2001) Cardiovascular risk factors, including thrombotic variables, in a population with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 40: 640–644

Eurenius E and Stenstrom CH (2005) Physical activity, physical fitness, and general health perception among individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 53: 48–55

Goodson NJ et al. (2005) Cardiovascular admissions and mortality in an inception cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis with an onset in the 1980s and 1990s. Ann Rheum Dis 64: 1595–1601

Solomon DH et al. (2004) Cardiovascular care and cancer screening in female nurses with and without rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 51: 429–432

Pitsavos C et al. (2005) The associations between physical activity, inflammation, and coagulation markers, in people with metabolic syndrome: the ATTICA study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 12: 151–158

Haagsma CJ et al. (1999) Influence of sulphasalazine, methotrexate, and the combination of both on plasma homocysteine concentrations in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 58: 79–84

Egan KM et al. (2005) Cyclooxygenases, thromboxane, and atherosclerosis: plaque destabilization by cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition combined with thromboxane receptor antagonism. Circulation 111: 334–342

Yanovski JA and Cutler GB Jr (1994) Glucocorticoid action and the clinical features of Cushing's syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 23: 487–509

Kiortsis DN et al. (2005) Effects of infliximab treatment on insulin resistance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 64: 765–766

van Ede AE et al. (2002) Homocysteine and folate status in methotrexate-treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 41: 658–665

Choi HK et al. (2002) Methotrexate and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study. Lancet 359: 1173–1177

Jacobsson LT et al. (2005) Treatment with tumor necrosis factor blockers is associated with a lower incidence of first cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 32: 1213–1218

Hurlimann D et al. (2002) Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha treatment improves endothelial function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation 106: 2184–2187

Hansel S et al. (2003) Endothelial dysfunction in young patients with long-term rheumatoid arthritis and low disease activity. Atherosclerosis 170: 177–180

Coletta AP et al. (2002) Clinical trials update: RENEWAL (RENAISSANCE and RECOVER) and ATTACH. Eur J Heart Fail 4: 559–561

Kwon HJ et al. (2003) Case reports of heart failure after therapy with a tumor necrosis factor antagonist. Ann Intern Med 138: 807–811

Bernatsky S et al. (2005) Anti-rheumatic drug use and risk of hospitalization for congestive heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 44: 677–680

Grigor C et al. (2004) Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 364: 263–269

van Gestel AM et al. (1996) Development and validation of the European League Against Rheumatism response criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Comparison with the preliminary American College of Rheumatology and the World Health Organization/International League Against Rheumatism criteria. Arthritis Rheum 39: 34–40

Greenfield JR et al. (2004) Obesity is an important determinant of baseline serum C-reactive protein concentration in monozygotic twins, independent of genetic influences. Circulation 109: 3022–3028

Pearson TA et al. (2002) AHA guidelines for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and stroke: 2002 update. Consensus panel guide to comprehensive risk reduction for adult patients without coronary or other atherosclerotic vascular diseases. American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee. Circulation 106: 388–391

Grundy SM et al. (2004) Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation 110: 227–239

de Jong Z and Vlieland TP (2005) Safety of exercise in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 17: 177–182

Andersen RE et al. (2002) Physiologic changes after diet combined with structured aerobic exercise or lifestyle activity. Metabolism 51: 1528–1533

McCarey DW et al. (2004) Trial of Atorvastatin in Rheumatoid Arthritis (TARA): double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 363: 2015–2021

Van Doornum S et al. (2004) Atorvastatin reduces arterial stiffness in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 63: 1571–1575

The National Cholesterol Education Program: Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) [www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/cholesterol/] (accessed 17 March 2006)

Nasir K et al. Comprehensive coronary risk determination in primary prevention: an imaging and clinical based definition combining computed tomographic coronary artery calcium score and national cholesterol education program risk score. Int J Cardiol, in press

Kumeda Y et al. (2002) Increased thickness of the arterial intima–media detected by ultrasonography in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 46: 1489–1497

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by an American College of Rheumatology Clinical Investigator Fellowship Award (JT Giles), an Arthritis National Research Foundation Award (JT Giles), and a grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (JM Bathon).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

JT Giles has declared no competing interests. W Post has received honoraria from Merck and Pfizer. R Blumenthal has received honoraria from Merck, Pfizer, Schering Plough, Astra Zeneca and KOS Pharmaceuticals. JM Bathon receives grant support from the National Institutes of Health, Bristol Myers Squibb, Centocor, Amgen, IDEC/Biogen and Roche, and is a consultant to Abbott Laboratories and Biowa.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giles, J., Post, W., Blumenthal, R. et al. Therapy Insight: managing cardiovascular risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2, 320–329 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncprheum0178

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncprheum0178

This article is cited by

-

Overview of vasculitis and vasculopathy in rheumatoid arthritis—something to think about

Clinical Rheumatology (2013)

-

Major trends in the manifestations and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in a multiethnic cohort in Singapore

Rheumatology International (2013)

-

Molecular genetic studies of gene identification for sarcopenia

Human Genetics (2012)

-

Managing cardiovascular risk in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases

Clinical Rheumatology (2012)

-

Endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction in rheumatic disease

Nature Reviews Rheumatology (2009)