Abstract

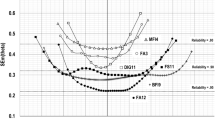

Fatigue is a common symptom among cancer patients and the general population. Due to its subjective nature, fatigue has been difficult to effectively and efficiently assess. Modern computerized adaptive testing (CAT) can enable precise assessment of fatigue using a small number of items from a fatigue item bank. CAT enables brief assessment by selecting questions from an item bank that provide the maximum amount of information given a person's previous responses. This article illustrates steps to prepare such an item bank, using 13 items from the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue Subscale (FACIT-F) as the basis. Samples included 1022 cancer patients and 1010 people from the general population. An Item Response Theory (IRT)-based rating scale model, a polytomous extension of the Rasch dichotomous model was utilized. Nine items demonstrating acceptable psychometric properties were selected and positioned on the fatigue continuum. The fatigue levels measured by these nine items along with their response categories covered 66.8% of the general population and 82.6% of the cancer patients. Although the operational CAT algorithms to handle polytomously scored items are still in progress, we illustrated how CAT may work by using nine core items to measure level of fatigue. Using this illustration, a fatigue measure comparable to its full-length 13-item scale administration was obtained using four items. The resulting item bank can serve as a core to which will be added a psychometrically sound and operational item bank covering the entire fatigue continuum.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Cella D. Factors influencing quality of life in cancer patients: Anemia and fatigue. Sem Oncol 1998; 25: 43–46.

Cella D, Passik S, Jacobsen P, Breitbart W. Progress toward guidelines for the management of fatigue. Oncology 1998; 12: 369–377.

Mooney K, Ferrel B, Nail L, et al. Oncology Nursing Society research priorities survey. Oncol Nurs Forum 1991; 18: 1381–1388.

Stetz K, Haberman M, Holcombe J, et al.Oncology Nursing Society research priority survey. Oncol Nurs Forum 1994; 22: 785–789.

World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief and palliative care. WHO, Geneva (technical report series 804), 1990.

Stone P, Richardson A, Ream E, Smith AG, Kerr DJ, Kearney N. Cancer-related fatigue: Inevitable, unimportant and untreatable? Results of a multi-centre patient survey. Ann Oncol 2000; 11: 971–975.

North American Nursing Diagnosis Association. Nursing diagnoses: Definition and classification, 1997-1998. Philadelphia, PA: McGraw-Hill, 1996.

Cella D, Davis K, Breitbart W, Curt G. Cancer-related fatigue: Prevalence of proposed diagnostic criteria in a United States sample of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 3385–3391.

Evans W. Functional and metabolic consequences of sarcopenia. J Nutr 1997; 127: 998S–1003S.

Fiatarone MA, Marks EC, Ryan ND, Meredith CN, Lipsitz LA, Evans WJ. High-intensity strength training in nonagenarians. Effects on skeletal muscle. JAMA 1990; 263: 3029–3034.

Cella D. Manual of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system. Evanston, IL: Center on Outcomes, Research and Education (CORE), Evanston Northwestern Healthcare and Northwestern University, 1997.

Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997; 13: 63–74.

Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, et al. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: Use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer 1999; 85: 1186–1196.

Piper BF, Dibble SL, Dodd MJ, Weiss MC, Slaughter RE, Paul SM. The revised Piper Fatigue Scale: Psychometric evaluation in women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 1998; 25: 711–717.

Smets EMA, Garssen B, Bonke B, DeHaes JCJM. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychom Res 1995; 39: 315–325.

Hann DM, Jacobsen PB, Azzarello LM, et al. Measurement of fatigue in cancer patients: development and validation of the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. Qual Life Res 1998; 7: 301–310.

Choppin B. Item bank using sample-free calibration. Nature 1968; 219: 870–872.

Choppin B. Guessing the answer on objective tests. Br J Educ Meas 1975; 45: 206–213.

McArthur DL, Choppin B. Computerized diagnostic testing. J Educ Meas 1984; 21: 391–397.

Weiss DJ, Kingsbury GG. Application of computerized adaptive testing to educational problem. J Educ Meas 1984; 21: 361–375.

Baek S-G. Computerized adaptive testing using the partial credit model for attitude measurement. In: Wilson M, Engelhard G. & Draney K. (eds), Objective Measurement IV: Theory into Practice. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1997; 37–55.

Wright BD. Negative information. Rasch Measur Trans 1996; 10: 504.

Baker FB. The basics of item response theory. ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation. College park, MD: University of Maryland, 2001.

Adema JJ, Boekkooi-Timminga E, Gademann AJRM. Computerized test construction. In: Wilson M. (ed), Objective Measurement I: Theory into Practice. Norwood, NJ: Ablex, 1992; 261–273.

Bergstrom BA, Lunz ME. Confidence in pass/fail decisions for computer adaptive and paper-and-pencil examination. Eval Health Profess 1992; 15: 453–464.

Bunderson CV, Inouye DK, Olsen JB. The four generations of computerized educational measurement. In: Linn RL (ed) Educational Measurement, 3rd ed. The American Council on Education/Macmillan series on higher education. New York, NY: American Council On Education, Macmillan Publishing Co; 1989; 367–407.

Reckase MD. Adaptive testing: The evolution of a good idea. Educ Measure Issue Prac 1989; 8: 11–15.

Butcher JN. Computerized clinical and personality assessment using the MMPI. In: Butcher JN (ed), Computerized Psychological Assessment: A Practitioner's Guide. NY: Basicbooks; 1987; 161–197.

Ware JE, Bjorner JB, Kosinski M. Practical implications of item response theory and computerized adaptive testing: A brief summary of ongoing studies of widely used headache impact scales. Med Care 2000; 38(Suppl. II): II73–II82.

Cella D, Chang C-H. A discussion of item response theory and its applications in health status assessment. Med Care 2000; 38(Suppl. II): II66–II72.

Hays RD, Morales LS, Reise SP. Item response theory and health outcomes measurement in the 21st century. Med Care 2000; 38: II28–II42.

Hambleton RK. Principles and selected applications of item response theory. In: Linn RL (ed) Educational measurement 3rd ed. NY: American Council on Education; 1989: 147–200.

Demetri GD, Kris M, Wade J, Degos L, Cella D. Quality-of-life benefit in chemotherapy patients treated with Epoetin Alfa is independent of disease response or tumor type: Results from a prospective community oncology study. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 3412–3425.

Cella D. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Anemia (FACT-An) Scale: A new tool for the assessment of outcomes in cancer anemia and fatigue. Seminars in Hematology (Suppl) 1997; 34: 13–19.

Cella DF, Lai J-S, Chang C-H, Peterman, A. Fatigue in cancer patients compared to that of the general United States population. Cancer 2002; 94: 528–538.

Groopman JE, Itri LM. Chemotherapy-induced anemia in adults: Incidence and treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999; 91: 1616–1634.

Massey JT, Botman SL. Weighting Adjustments for Random Digit Dialed Surveys In Telephone Survey Methodology. New York: James Wiley and Sons, 1988; 143–160.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-12: How to score the SF-12 physical and mental summary scales. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, 1995.

Bode R. Understanding Rasch measurement: Partial credit model and pivot anchoring. J Applied Measurement 2000; 2: 78–95.

Andrich D. A rating formulation for ordered response categories. Psychometrika 1978; 43: 561–573.

Linacre JM. WINSTEPS-Rasch analysis for all two-facet models. Chicago: MESA Press, 2000.

Angoff WH. Perspectives on differential item functioning methodology. In: Holland PW, Wainer H (eds), Differential item functioning. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 1993; 3–24.

Wright BD, Panchapakesan N. A procedure for sample-free item analysis. MESA research memoranda # 46. Chicago: MESA Press, 1969.

Linacre M. Sample Size and Item Calibration Stability. Rasch Measurement Transaction 1994; 7: 328.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lai, Js., Cella, D., Chang, CH. et al. Item banking to improve, shorten and computerize self-reported fatigue: An illustration of steps to create a core item bank from the FACIT-Fatigue Scale. Qual Life Res 12, 485–501 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025014509626

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025014509626