Abstract

Background

Randomised, controlled trials (RCT) and systematic reviews of RCT with meta-analysis are considered to be of highest methodological quality and therefore are given the highest level of evidence (Ia/b). Although, “low-quality” RCT may be downgraded to level of evidence IIb, the methodological quality of each individual RCT is not respected in detail in this classification of the level of evidence.

Materials and methods

Within a systematic Cochrane Review of RCT on short-term benefits of laparoscopic or conventional colorectal resections, the methodological quality of all included RCT was evaluated. All RCT were assessed by the Evans and Pollock questionnaire (E and P increasing quality from 0–100) and the Jadad score (increasing quality from 0–5).

Results

Publications from 28 RCT printed from 1996 to 2005 were included in the analysis. Methodological quality of RCT was only moderate [E & P 55 (32–84); Jadad 2 (1–5)]. There was a significant correlation between the E & P and the Jadad score (r = 0.788; p < 0.001). Methodological quality of RCT slightly increased with increasing number of patients included (r = 0.494; p = 0.009) and year of publication (r = 0.427; p = 0.03). Meta-analysis of all RCT yielded clinically relevant differences for overall and local morbidity when compared to meta-analysis of “high-quality” (E & P > 70) RCT only.

Conclusion

The methodological quality of reports of RCT comparing laparoscopic and open colorectal resection varies considerably. In a systematic review, methodological quality of RCT should be assessed because meta-analysis of “high-quality” RCT may yield different results than meta-analysis of all RCT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Methodological quality of clinical trials is usually described according to the rules of evidence-based medicine. Within this system, systematic reviews with meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCT) and single homogeneous RCT do achieve the highest possible “level of evidence” (Level 1) and “grade of recommendation” (Grade A). Despite the fact that RCT of “poor quality” [1–3] may be judged only with “level of evidence” 2a and “grade of recommendation” B, methodological quality of RCT is not considered in detail in this classification. Because results of RCT or meta-analysis of RCT may be directly transferred into clinical practice, “critical appraisal” of these trials is essential.

In colorectal surgery, the scientific debate concerning the benefits of laparoscopic or conventional colorectal resections was targeted by a systematic Cochrane Review of RCT [4]. In addition to the results of this review, which have been published in the Cochrane Library [4], a systematic assessment of the retrieved reports of RCT was performed using validated instruments. The goal of this assessment was to define the methodological quality of the reports and its association to sample size, year of publication or impact factor of the publishing journal. In addition, we wanted to evaluated whether meta-analysis of all RCT would yield different results than meta-analysis of “high-quality” RCT only.

Materials and methods

Systematic review of the literature and search strategy

From 2003 to 2004, a systematic literature search according to the guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration was performed to identify RCT that assess possible short-term benefits of laparoscopic compared to conventional colorectal resections. Details of the systematic electronic search and hand search of the literature from 1991 to 2004 were reported in the final version of the Cochrane Review published online in 2005 [4]. In brief, we searched the Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group Trials Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Medline, Embase, and Cancerlit. The Cochrane Collaboration’s highly sensitive search strategy for RCT was combined with the following MeSH terms: colon*, colectomy*, proctectomy*, intestine-large*, colonic neoplasm*, rectal neoplasm*, laparosc*. We hand searched the following medical journals: British Journal of Surgery, Archives of Surgery, Annals of Surgery, Surgery, World Journal of Surgery, Disease of Colon and Rectum, Surgical Endoscopy, International Journal of Colorectal Disease, Langenbeck’s Archives of Surgery, Der Chirurg, Zentralblatt für Chirurgie, Aktuelle Chirugie and Viszeralchirurgie. Abstracts from the following society meetings were hand searched: American College of Surgeons, American Society of Colorectal Surgeons, Royal Society of Surgeons, British Association of Coloproctology, Surgical Association of Endoscopic Surgeons, European Association of Endoscopic Surgeons and Asian Society of Endoscopic Surgeons. There was no systematic review of the literature of 2005, but 3 RCT [5–7] published in 2005 that we became aware of were also included in this analysis.

Data extraction, inclusion and exclusion of trials

Data extraction and quantitative data synthesis were performed according to the Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group’s guidelines. As potential predictive factors for methodological quality for each report, the year of publication, number of participating patients and impact factor (ISI Web of KnowledgeSM, http://www.portal.isiknowledge.com; JCR 2005) were retrieved. Eligibility criteria for trials were RCT (pseudo-randomised trials as well as studies that followed patient’s preferences were excluded); trials had to compare conventional and laparoscopic colorectal resection for either benign or malign disease (studies evaluating hybrid technologies like hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery were excluded); trials had to report clinical outcomes (trials only reporting immunological or other laboratory data without any clinical outcome parameters were excluded).

Assessment of methodological quality of RCT

All manuscripts were independently assessed by three reviewers (W.S., O.H. and J.N.), disagreements were resolved by discussion. Methodological quality of included RCT was judged by a modified Evans and Pollock questionnaire [8] (E & P, Table 1) and the Jadad score [9] (Table 2). The E & P questionnaire was originally developed to assess methodological quality of RCT on prophylaxis of abdominal surgical wound infection. However, after minor modifications, this score was adopted to evaluate methodological quality of RCT concerning laparoscopic or conventional colorectal resection.

The E & P questionnaire contains 33 questions concerning study design, data analysis and presentation of data (Table 1). All questions can be answered by “yes” or “no”. A “no” scored 0 points and a “yes” between 1 and 5 points. The study design was covered by 15 questions (yielding 0–50 points), data analysis by 10 questions (0–30 points) and presentation of data by 8 questions (0–20 points). In total, a maximum of 100 points may be scored by a report of a methodologically perfect RCT. It was agreed between the reviewers that methodological quality of a publication would be graded as good (70–100 points), moderate (50–70 points) or poor (less than 50 points) according to the E & P score. The Jadad questionnaire comprises only three questions that concern randomisation, blinding and patients excluded (Table 2). This score ranges from 0 (worst) to 5 (best methodological quality).

Methodological quality and results of the meta-analysis

To investigate whether a selective meta-analysis of RCT with high methodological quality would yield different results from the meta-analysis of all RCT included into the systematic review, data for overall, general and local (surgical) morbidity were pooled for either all RCT or only for those RCT that scored more than 70 points in the E & P questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

All data were documented in SPSS 13.0® for Windows XP (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Correlation between continuous data was assessed by Pearson’s test. Details of the process of meta-analysis were published in the Cochrane Library [10]. In brief, for dichotomous variables, rate differences with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. We pooled effect measures within random effects models [11] and calculated risk reduction (RR), 95%CI, relative risk reduction (RRR), absolute risk reduction (ARR) and the number of patients that need to be treated to prevent one complication (NNT). In general, p values < 0.05 were considered significant. Continuous data are presented as median and range.

Results

Methodological quality of RCT

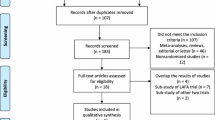

Systematic hand search and electronic search of the literature yielded 41 reports of RCT comparing the short-term post-operative course after laparoscopic or conventional colorectal resection. Thirteen publications were excluded because of later publications from the same trial concerning the same or greater number of patients (n = 8), the publications did not contain any clinical outcome data (n = 1), pseudo randomisation was performed (n = 1) or technical details of laparoscopic colorectal surgery or evaluation of hybrid techniques (like hand assisted laparoscopic surgery; n = 3) were investigated. A total of 28 reports of RCT were included into final evaluation. Characteristics of these publications are given in Table 3. None of the investigated RCT achieved the full E & P score. Positive answers ranged from only 3 (11%; question 24: “Data of test statistic and probabilities given?”) to 27 (96%; question 32: Results believable?) studies (Fig. 1). Median overall E & P score for all 28 RCT was 57 (26–93), while RCT scored 27.5 (0–50) of 50 points for study design, 13 (0–26) of 30 points for data analysis and 15 (5–18) of 20 points for presentation of data. In relation to the maximum scores for each of the three segments of the E & P questionnaire, the RCT scored significantly worse for study design [55 (0–100)% of possible score] and data analysis [43 (0–87)%] than for data presentation [75 (25–90)%; overall Kruskal–Wallis p = 0.001]. RCT scored 2 (1–5) in the Jadad score, with one RCT scoring 5 points, 11 (40%) only 1 point and 10 (35%) 2 points. Seven of 28 (25%) reports from RCT scored 70 points or more in the E & P questionnaire and were considered to be of high methodological quality. The Jadad score of these “high-quality” RCT was 3 (1–5). Thirteen (46%) reports were of moderate [E & P 57 (52–69), Jadad 2 (1–3)] and 8 (29%) reports of poor quality [E & P 37 (26–49), Jadad 1 (1–2)]. “High-quality” reports of RCT yielded significantly higher Jadad scores than “moderate-quality” or “poor-quality” reports (p = 0.003).

Correlation between E & P and Jadad score was high (r = 0.62; p = 0.0004) Interestingly, total E & P score was not correlated to either year of publication (r = 0.19; p = 0.3) or number of patients recruited (r = 0.09; p = 0.62). Jadad score slightly increased with increasing year of publication (r = 0.43; p = 0.02), but larger RCT were not associated with higher Jadad scores (r = 0.22; p = 0.24). E & P scores increased significantly with increasing impact factor of the journal that had published the report (p = 0.04), but correlation was rather weak (r = 0.38), and “high-quality” reports were not published in journals with a significantly higher impact factor [3.7 (2.2–23.4)] than “medium-quality” [3.7 (0–23.4)] or “low-quality” [1.8 (1.1–3.7)] reports (p = 0.17). There was no correlation between Jadad score and journal impact factor (r = 0.36; p = 0.16).

Methodological quality and result of meta-analysis

Forrest plot and statistical parameters of pooled data for overall morbidity, general (medical) morbidity and local (surgical) morbidity are given in Figs. 2, 3, and 4. Meta-analysis of all RCT for overall morbidity included reports from 21 RCT including 2,581 laparoscopic and 2,284 conventional patients. Five hundred and fifty-four laparoscopic patients (21.5%) experienced post-operative complications compared to 553 conventional patients (23.2%). The RR was 0.81 (95%CI 0.66, 0.99; p = 0.04), RRR was 7.3%, ARR 1.7%, and NNT to prevent one adverse post-operative event was 59. Data on overall morbidity was given in all seven “high-quality” reports of RCT and included 896 laparoscopic and 894 conventional patients. There were 188 post-operative complications after laparoscopic surgery (21.0%) and 222 complications after conventional resection (24.8%). RRR and ARR were 15.3 and 3.8%, respectively. Compared to the meta-analysis from all 28 RCT, RR remained almost unchanged (0.80), but the difference between laparoscopic and conventional surgery was not significant anymore (p = 0.28; Fig. 2).

Data concerning general (medical) morbidity was specified in 13 reports of RCT on 927 laparoscopic and 924 conventional patients. Sixty-two laparoscopic patients (6.7%) and 77 conventional patients (8.3%) experienced a medical complication. RR was 0.83 (0.61; 1.14; p = 0.26). RRR was 19.2%, and ARR was 1.6%. Five of 7 “high-quality” reports from RCT gave data on medical morbidity, which occurred in 23 of 365 laparoscopic (6.3%) and 29 of 356 conventional (8.1%) patients. RR was 0.78 (0.46; 1.31; p = 0.35). RRR and ARR were 22 and 1.8%, respectively.

Surprisingly, only 13 reports gave information on local (surgical) morbidity, which was observed in 74 of 862 laparoscopic (8.6%) and 141 of 850 conventional (16.6%) patients when all 28 RCT were considered. RR by laparoscopic surgery was 0.55 (95%CI 0.39, 0.77; p < 0.0001), RRR 48% and ARR 8.0%, resulting in NNT of 12.5. Four of seven “high-quality” reports reported local morbidity in 35 of 336 laparoscopic (10.4%) and 81 of 327 conventional (24.8%) patients. RR for local morbidity was larger 0.42 (0.29; 0.61) in “high-quality” reports than in all 28 reports, and RRR (58.1%) and ARR (14.4%) increased, causing the NNT to be halved (6.9) when compared to the meta-analysis of all 28 RCT (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Twenty-one of 28 reports of RCT (75%) comparing short-term outcome of laparoscopic or conventional colorectal resection showed moderate to poor methodological quality when assessed with the E & P questionnaire. Methodological quality of the manuscripts did not increase with year of publication or number of patients included but showed a weak correlation to the journal impact factor. Meta-analysis of overall and local (surgical) complications of all 28 RCT compared to those 7 RCT with high methodological quality displayed clinically relevant differences. Therefore, systematic reviews of RCT should provide detailed information concerning the methodological quality of their individual RCT.

RCT have the highest methodological quality of all clinical trials because randomisation avoids several types of bias [12]. Unlike the results of basic or animal research, the results of clinical RCT may be transferred to clinical practice immediately. Therefore, quality assessment of individual reports of RCT summarised in a systematic review is necessary to limit bias in conducting the systematic review and guide interpretation of findings. Numerous instruments to scale the quality of RCT have been developed [13, 14], but no international standard exists. Most of the available scales for assessing the validity of RCT derive a summary score by adding the scores (with or without differential weights) for each item. While this approach offers appealing simplicity, it is not without problems [15, 16]. For this analysis, we applied the E & P and the Jadad questionnaire, both resulting in a score system (Table 1 and 2). The Jadad’s score is a very simple but validated tool to assess the basic quality of an RCT (randomisation described and adequate; blinding described and adequate; exclusions stated), while the E & P score provides much more detailed information regarding the different aspects of methodological quality of the manuscript. However, the high correlation between the Jadad and the E & P score demonstrate that both instruments relate to similar aspects of methodological quality of RCT.

In general, there are two major difficulties with assessing the methodological quality of studies. First, a low score for an RCT may result because important details of the study design (i.e. concealment of randomisation or blinding), although performed, were simply not reported in the manuscript. On the other hand, it is possible to assume that something that was not reported was not done. However, this may not be the truth, and the only way to find out is to obtain additional information from the investigators. During the process of this review, all primary authors were contacted, but only one responded to our questions. The problem of inadequate reporting of study details is targeted by the CONSORT statement, which was adopted by most of the major peer-reviewed medical journals since 1996. Recently, Plint et al. [17] demonstrated that the quality of reports of RCT actually improved with the adaptation of the CONSORT checklist. All RCT in our systematic review were published after 1995, but only very few did follow the CONSORT recommendations. Therefore, it cannot be ruled out that inadequate reporting is a reason for the low to medium methodological quality of the most analysed RCT.

The second limitation in assessing the methodological quality of RCT is limited evidence of a relationship between quality and actual study outcomes. Basically, inadequate concealment of allocation or lack of double blinding will result in overestimates of the effects of treatment [18]. Our analysis of overall, general and local morbidity after laparoscopic or conventional colorectal resection displayed three possible results of a meta-analysis restricted to “high-quality” studies only. (1) Meta-analysis of all RCT and of “high-quality” RCT yields similar results (Fig. 2). (2) Meta-analysis of “high-quality” reports compared to all reports increase the 95%CI due to decreased number of patients, and statistical significance of the effect estimate is lost (Fig. 3). (3) Meta-analysis of “high-quality” reports compared to all reports may result in different event rates and change the effect estimate (RR) as well as its 95%CI (Fig. 4).

In conclusion, our results and other reports from the literature clearly demonstrate that more research needs to be done to establish which criteria for assessing methodological quality of RCT are indeed important determinants of study results. Systematic assessment of publications of RCT identified in a systematic review of the literature comparing short-term results of laparoscopic or open colorectal resection revealed profound differences in methodological quality. Although there is no uniform agreement on one instrument to assess methodological quality of RCT, authors of systematic reviews of RCT should use at least one instrument to provide the readers with information on the average methodological quality of the RCT included in the review. Readers should be aware of the fact that although a randomised controlled study design was chosen, methodological quality of RCT may be poor, and adoption of the results of any RCT warrants careful “critical appraisal” not only of the data but also of details of the study design.

References

Sackett DL (1986) Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations on the use of antithrombotic agents. Chest 89(2):S2–S3

Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, Laupacis A, Sackett DL (1992) Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations on the use of antithrombotic agents. Chest 102(4):S305–S311

Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (2005) Levels of evidence and grades of recommendation. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine; http://www.cebm.net/levels_of_evidence.asp#levels.

Schwenk W, Haase O, Neudecker J, Muller JM (2005) Short term benefits for laparoscopic colorectal resection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3):CD003145

Basse L, Jakobsen DH, Bardram L, Billesbolle P, Lund C, Mogensen T et al (2005) Functional recovery after open versus laparoscopic colonic resection: a randomized, blinded study. Ann Surg 241(3):416–423

Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, Walker J, Jayne DG, Smith A et al. (2005) Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 365:1718–1726

The Colon Cancer Open or Laparoscopic Study Group (COLOR) (2005) Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: short-term outcomes of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 6:477–484

Evans M, Pollock AV (1985) A score system for evaluating random control clinical trials of prophylaxis of abdominal surgical wound infection. Br J Surg 72:256–260

Jadad A, Moore A (1996) Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blindness necessary? Control Clin Trials 17:1–12

Alderson P, Green S, Higgins JPT (2004) Cochrane Reviewer’s Handbook 4.2.2. Wiley, Chichester, UK, (updated March 2004)

DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7:177–188

Spilker B (1991) Guide to clinical trials, 1st ed. Raven Press

Moher D, Jadad AR, Tugwell P (1996) Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials. Current issues and future directions. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 12(2):195–208

Moher D, Jadad AR, Nichol G, Penman M, Tugwell P, Walsh S (1995) Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials: an annotated bibliography of scales and checklists. Control Clin Trials 16(1):62–73

Emerson JD, Burdick E, Hoaglin DC, Mosteller F, Chalmers TC (1990) An empirical study of the possible relation of treatment differences to quality scores in controlled randomized clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 11(5):339–352

Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG (1995) Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 273(5):408–412

Plint AC, Moher D, Morrison A, Schulz K, Altman DG, Hill C et al (2006) Does the CONSORT checklist improve the quality of reports of randomised controlled trials? A systematic review. Med J Aust 185(5):263–267

Moher D, Pham B, Jones A, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Moher M et al. (1998) Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet 352(9128):609–613

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors state that there are no commercial or other associations that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with submitted material. There was no external funding of any kind supporting the work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper was presented during the Surgical Forum of 122nd Congress of the German Surgical Society in Berlin in May 2006.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schwenk, W., Haase, O., Günther, N. et al. Methodological quality of randomised controlled trials comparing short-term results of laparoscopic and conventional colorectal resection. Int J Colorectal Dis 22, 1369–1376 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-007-0318-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-007-0318-7